It was when they pulled out the machetes that I started to worry.

I’d seen men with machetes in Africa before, but they were rusty, practical tools used for clearing away brush by the side of the highway. These were long, shiny and housed in decorative sheaths, pulled out ostensibly so the men could sit down more comfortably, but done with a clear, understated flair. They were more like sultan swords than jungle tools.

The kicking in my six-month pregnant belly had gone eerily silent since we entered the vigilante court at Alaba. I reassured myself that I’d been through things like this before. The time I went to visit Brazilian entrepreneur Marco Gomes’ hometown in the crime-ridden slums of central Brazil, comforted only by his reassurance that “No foreigner has ever died in my hometown, because no foreigner has ever been to my hometown.” And the time I was driving along the boarder between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo and armed Rwandan guards stopped our car, wordlessly got in the backseat and hitched a ride for several miles. And then there was the time we were charged by a baboon.

Looking at those beady baboon eyes rushing towards me, I was instantly convinced I was losing an arm. Now, in this Nigerian “courtroom,” my husband was looking at the machetes having the same thought. I was just hoping they didn’t realize he’d slipped the camera’s memory card in his pocket. I tried to pat my stomach as apologetically as I could. Sorry, son. Welcome to life as my kid.

Sometimes I write provocative leads that aren’t quite what they seem. Like the time I said I was in a wheelchair getting a blood transfusion in Singapore. As the second graph explained, I was actually at a hospital-themed bar where you sit in wheelchairs and drink out of IV bags. My cocktail was called a “blood transfusion.”

But this time, I’m not being hyperbolic or clever. There’s no twist coming. My husband, our unborn child and I were actually sitting in a Nigerian vigilante court being tried for– as near as I could tell– taking photos and not respecting authority. The makeshift courthouse looked like a set of a Western. The judge was named “Bones.” The police? Well, there was a station not too far from here, but the police ceded Bones authority in Alaba. They didn’t what to get involved.

It could have been a scene in a movie. That irony wasn’t lost on us, because our accusers, the people speaking for us, and the judge, jury and — well, let’s just call them the guys with the machetes– were there to protect the interests of the rough-and-tumble world of the Nigerian filmmaking. They call it Nollywood.

Nollywood sprung up a few decades ago and is the second largest film industry in the world by volume. Producers churn out hundreds of movies a month, most shot on a shoe-string budget of $10,000 or less. We visited a set of a film called “The Stripers.” It reminded me of the photos in Larry Sultan’s book about low-frills porn sets, “The Valley,” sans sex and nudity of course.

The film– a romantic comedy where one of Nollywood’s hottest actresses turns a gay man straight– was shot in an empty suburban house rented for a few days with a crew of no more than ten. The assistant did the hair and makeup, and the producer did most everything else.

There are few theatrical releases in Nollywood. Most of these movies– which Nigerians consume as rabidly as Brazilians devour their telenovelas– are seen on local TV stations and sold over DVDs. And these producers move fast: Last week we saw a movie on the market called “Dead at Last: Osama Bin Laden, Complete Season One: Life and Death.”

Like most industries in emerging markets, Nollywood is developing in a very different time than Hollywood or even Bollywood developed, and that alone means it’s developing in a very different way. On the plus side, cheap modern digital production tools have made it all possible. But rampant digital piracy means there’s no honeymoon period for producers to build an industry around protected copyrights. They produce content millions of people love, but most of these scrappy street producers are constantly operating on shoe-string budgets, lucky to break even on each film.

Alaba International Market is where the producers all have their store-fronts and distribution hubs. We met dozens of them inside a long, dark cave-like hallway where each producer operated out of a cell-sized office, filled with paper records, movie posters pasted over movie posters, and spindles of thousands of DVDs.

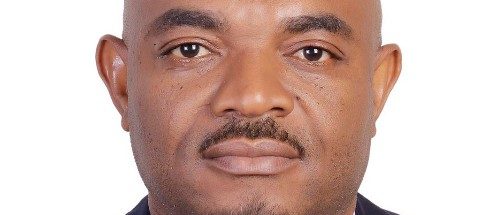

Some of these producers are highly-educated entrepreneurs following their passion the same way the best entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley have. We met one man named Ulzee, a Nollywood pioneer who decided to make movies after getting a science degree. (Pictured right.) His wife, trained as a lawyer, joined him along the seemingly crazy journey. His biggest hit was “Osuofia in London,” one of the first Nollywood films to get international attention. He shot it on location in London and it cost about $6,500 to make– a jaw-dropping investment for a Nollywood picture back in 2003. But it grossed more than $650,000.

Much like the 419 scam business, members of Nigeria’s 50 million-person unemployed class see the glamorous, seemingly easy money of Nollywood and have flooded into the business. Ulzee doesn’t respect many of them, saying they aren’t artists. They shoot once and release the same movie with four different covers just to make an extra buck. Of course, given the rampant piracy that’s destroyed their margins, you can understand why these producers are constantly trying to milk revenues out of the same film.

Here’s what makes the mood at the Alaba market so tense: Before you get to that hallway of producers peddling their movies in their cell-like offices, you walk past the open air markets where the software and DVD pirates have set up shop. Unlike Hollywood where the producers reside in glamourous offices and pirates operate the the shadows and basements of the Internet, in Alaba the content creators and those destroying their hopes of revenues reside in the same place, selling the same product side-by-side. Fire-and-brimstone evangelical preachers set up keyboards and microphones in the middle of the street to save souls, only adding to the chaos. (Video of some of this in the next post.) So I could understand why Bones and his council occasionally need some machetes to keep the peace.

After 40 weeks in emerging countries, markets tend to blur together, but Alaba was unlike any place I’ve seen before. It was rawly and intensely Nigerian. Nigeria isn’t a culture based on pleasantries. A local saying painted on the backs of trucks sums it up: “No Paddy for Jungle,” or no one has friends in the jungle.

And Lagos is like a jungle. On Victoria Island– the ritzy section of Lagos– incomes are high even for a dual economy, thanks to oil and corruption. The most basic four-star hotels cost upwards of $500 a night, and the rich buy up rooms for a whole year or more, artificially constricting supply. Plots of land cost millions and a middle-of-the-road dinner for two without drinks can run $100 or more. But on the mainland in Lagos, you see the real Nigeria, the one where one-third of the population is unemployed. I talked to people furious by the corruption in the country, and what they felt was an unfair nepotism among the rich that made it almost impossible to climb the societal ladder.

Even the people I met in “easy money” businesses such as scamming and Nollywood toil entrepreneur’s hours to build their fortunes, constantly under pressure to outsmart the people out to kill their livelihoods– whether that’s law enforcement in the case of scammers or pirates in the case of Nollywood.

The tension is palpable. Stuck in traffic on the freeways, we saw fist-fights break out. Unlike some other developing countries where hawkers will smile and flatter Westerners in an attempt to sell them outrageously priced goods, Nigerians don’t play that game. They’re happy to sell you something if you show the cash. Otherwise, keep moving. They have little use for smiling, nodding and pandering. It’s not necessarily that there’s more anger, resentment or corruption in Nigeria than the rest of the emerging world; Nigerians just wear it on their sleeves.

Part of me loves that. The warm hospitality many people showed us– in both poor and rich areas of the city– was genuine. You know where you stand in these places; it’s all out in the open. But it makes walking through these markets intimidating. Look at a hawker and smile on the wrong day, and you’ll get screamed at just for being there. As one 419 scammer told me, “If I can’t even trust a man with the black flesh, why should I ever trust you?”

Our guide through Nollywood was an entrepreneur named Jason Njoku (seen on the right in this photo, haggling with producers). His parents are Nigerian, but he grew up in the United Kingdom. He became entranced with Nollywood a few years ago and was bored with London. So he moved here, stunning his family and friends. He started Iroko Partners to catalog this vast Nollywood inventory and give it a new global distribution life on the Web. It sounds like a recipe for a city boy to get fleeced, but so far that hasn’t been the case.

Njoku spent weeks trolling the Alaba markets introducing himself to producers and trying to explain to them how a YouTube channel could be an answer for revenues, not simply another channel for the pirates to steal their intellectual property. Once he sold a few of the bigger ones like Ulzee, word spread and more producers piled in. Just four months in to his business, Njoku has bought the online rights to 500 movies from 100 different one-man production houses. Last month his YouTube channel had 1.1 million uniques, 8 million streams, and is on pace to do more than $1 million in revenues this year from YouTube ads. Those numbers are massive for a Nigerian-based Web company, particularly in such a short time. Facebook has one of the largest user-bases here, feeling ubiquitous in the city. And yet it has less than three million users.

Njoku is playing a long-game. Most of his traffic is from outside Nigeria, because broadband penetration is still so low there. He’s paying more than he would have to for rights; about $3,000 per film, roughly what TV stations pay. That immediately returns about one-third of the production costs, a welcome surprise for a new medium that most of these producers had never really considered before. He provides a lot of other value-added services too, like creating an IMDB-equivalent for the messy Nollywood industry, and watching all movies to strip out things like the unauthorized use of a Beyonce song. In the future, he’s going to provide French subtitles so the movies can find new audiences in surrounding West African nations.

The checks have endeared Njoku to this rag-tag community of producers. One of Njoku’s several cell phones rings constantly with producers calling him to check on contracts, release dates and when they’re getting their next checks.

And that loyalty came in handy about the time a screaming mob broke out in Alaba over the presence of two unknown Americans taking pictures. I’m still not sure if they actually thought we were spying on their business or just wanted to extort us for cash. I’m still not sure whether it was the pirates, the producers or other rabble rousers who were the instigators. The ring leader appeared to be a terrifyingly huge, enraged, bald guy wearing a tight, white muscle shirt that said “SKULL SHIT” in big letters.

We barricaded ourselves in Ulzee’s cell-like office until it died down. We didn’t have another choice. We were half way down a long, dark hallway of offices, and there was no way out without going through the mob. Ulzee’s wife, who’d been lounging on some boxes when we arrived, sprung into action, explaining to the accusers that we were their guests and welcome to do what we wanted.

Eventually, the chaos died down, we promised not to take anymore pictures and we tried to leave. But as soon as we left the office, it erupted again and the crowd encircled us. The screaming intensified, echoing through the cave-like hallway. I tried to go back into Ulzee’s office, but the doors were being locked behind me by Bones’ crew. We were trapped, and the angry faces were circling in tighter, the screaming unintelligible as it echoed from wall-to-wall.

“Trust me, it’s better that this plays out here than on the street,” Njoku said. “Half of the people yelling are on our side.”

News of the uproar reached Bones, the man entrusted to keep the peace between producers, pirates and rare interlopers like ourselves. And that’s when we were summoned to his court. A phalanx of producers escorted us through the streets making sure no more harm came to us before we got there. “Don’t worry,” Njoku whispered. “As long as I have my checkbook, they still need me alive.”

We sat on one bench. The producers sat on the other. And that’s when Bones and the machete-men strolled in. After hearing all the evidence, our insistence that we respected his authority, the producers vouching for us, and of course, some cash changed hands, the machetes stayed sheathed and they let us go.

Njoku didn’t break a sweat. Rather than convincing me he was trying to regulate something that couldn’t possibly be regulated, the whole episode made me more bullish on his company. It was clear how much the legitimate entrepreneurs in this community valued him, the depth of his relationships after just four months, and his innate understanding for navigating crisis in a terrifying situation.

If a businesss like this were being built in the West, there’d be few barriers to entry. Someone can always just pay higher license fees. But in a country like Nigeria, these sort of relationships, this kind of trust in a place where no one trusts anyone are more solid barriers to entry than patents.

The demand is there. The supply is there. Nollywood will emerge out of this chaos as something hugely profitable. There’s suspicion, competition and chaos surrounding the market, but that’s business in emerging markets. At the end of the day the producers weren’t unreasonable. They asked that next time Njoku bring guests, he give them a heads up and they’d provide protection. They’re justifiably suspicious because their industry is finally starting to take off, and they sit next to the people trying to eroding it every day. And my bet is that when Nollywood does take off, Njoku will be one of the guys to reap the benefits.

Of course, we couldn’t leave without pressing our luck and asking to take Bones & Co.’s picture. It’s below, and he’s on the bottom right. Note: Those smiles were nowhere to be seen before the cash changed hands.