Primitive’s Ghanaian movie posters showcase the splendor and madness of a particular kind of advertising

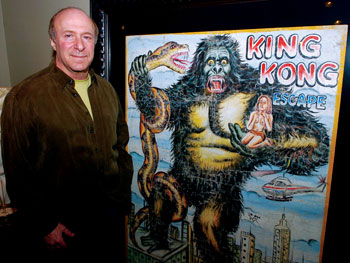

Glen Joffe wanted to show me something.

As the owner of Primitive, 130 N. Jefferson, an art gallery and store, Joffe had plenty of somethings to show me on all four floors. Unusual, beautiful and uncommon things — though “authentic” was his preferred adjective. Specifically, I visited earlier this year to see Primitive’s collection of 330 Ghanaian movie posters, some of the most beautifully, authentically, unusually, uncommon (though sometimes unlovely) objets d’art I’ve ever seen.

Primitive is as prettily scented and accessorized as an expensive girlfriend. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I didn’t belong there, and that at any moment I would topple and smash something worth more than my liver. Speaking in the store’s library — surrounded by Islamic glassware, Nepalese vases and Hindu statuary snuggled amidst tantric lingam stones — Joffe assured me Primitive welcomed all lovers of beauty.

“For years I would tell our staff the worst thing that can happen to anyone who appreciates beautiful things is to walk into a gallery or a space, and the person behind the counter turns their head and goes like this,” Joffe said, miming a disdainful nose tilt. “As if it’s some sacrosanct place. That’s not what you’ll find here.”

No, “sacrosanct” isn’t the right word; I’m thinking “exotic.” Primitive certainly presents an esoteric vibe. Joffe summarizes the stock as being from “the entire world, but here,” and confronted by the gallery’s plenitude of faraway goods, a visitor can feel ensconced in an eclectically decorated museum-manor wafting with international mystery. Take a mini-temple secreted away on the second floor, where a collection of Buddhas meditate beneath flickering candlelight. As Jack Kerouac wrote, “in tranced fixation dreaming upon object before you.” Yeah, what he said.

Too many spy and kung-fu flicks made me imagine a man in a white suit and eye-patch emerging from a secret door, stroking an iguana while intoning, “You have grown most troublesome, Mr. Kelly.” More likely he’d offer some Darjeeling tea and show me a darling little cho cho milk container. (Full disclosure: I found that on the Primitive Web site. I have no idea what the hell a cho cho is). And speaking of the interplay of low culture and high art, how about those Ghanaian posters?

Joffe ended our tour on the third floor, where the posters were stacked atop a long table. The plan was to show me scans of them, but a glitch led to us laying them out on the floor, one by one, the musty scent of burlap hanging thickly. The posters average about 3’ by 5’, the size of the sliced-opened flour sacks the sign-makers used as canvases. The image of a windmill is on the back of every poster, along with “Selected Hard Spring Wheat Flour: Milled by GMG Tema: Pride of the West.”

On the reverse side is the art, and that way lies madness.

Rifling through the 330 posters burned certain images on my brain: swinging axes, decapitations, giant guns, fanged she-demons and snakes. Lots and lots of snakes, even for movies without snakes in them.

Amidst Primitive’s upscale trappings, the posters seem visceral and tawdry. Each is a one-of-a-kind oil painting. Many are straight, almost bland representations of pre-existing film artwork, while the most striking ones wallow in blood and guts. All are poured through the colorful prism of Ghanaian art. For all their unsettling oddness though, the posters come from a fairly utilitarian background.

Back in the 1980s and ’90s, starting in the capital city of Accra, Ghana saw the emergence of a new industry: the mobile cinema. Armed with a TV, VCR, gas-powered generator and rack of videotapes, an entrepreneur would drive from village to village, setting up in clubs, restaurants, houses and outdoor lots, bringing the pictures to the locals for the price of a few Ghanaian cedi.

The films came from four corners of the world — Hong Kong action flicks, Bollywood features, Nigerian (aka “Nollywood”) movies, and American films of varying quality. “Hollywood B, C, D, and E — if you will — horror, action, and sci-fi movies, with an occasional hit thrown in,” as Joffe put it. He found a few of the posters on one trip. Then the rest found him.

“When it was discovered that I was really collecting these then they started coming out of the woodwork,” he explained. “I have one really key relationship in Ghana with a very important dealer, and he was sending people into the bush — meaning he’s sending people out for me. And then when I go there I pick them up.”

Going by the titles and imagery, the Ghanaians liked action, gore and high weirdness. Chick flicks were absent, and Clint Eastwood’s Escape from Alcatraz was the nearest thing to standard drama. I suspect many titles (mostly ones from India and Nigeria) are the best thing about their respective films. While munching their popcorn, the audience could enjoy movies like Cannibal Terror, Cruel Corpse Door and Dead Mary.

With no access to studio press kits, the showmen commissioned posters from local sign-makers, tacking the posters to plywood and hanging them near the impromptu theater. When the show was over, the posters were rolled up and toted to the next town. The sack’s durability and the oil paint’s resilience ensured a long life, though holes and patches show up in the more traveled posters, and the flour sack labels sometimes bleed through the art. Still, Joffe finds the threadbare posters and their lived-in look more compelling.

The artists received inspiration differently. Sometimes the painter saw the film. More often he worked from the VHS tape case art. Image recycling is shameless. Tom Cruise’s Lestat character from Interview with the Vampire shares space with the titular heroine of the vampire-hunter flick Bloodrayne for the queerly named The Fierce Ghost Eats Human Region. Just as often, the sign-maker had the film described to them, leading to an incredible amount of artistic license in the drive to make the film look as awesome as possible. Tiny heads plug up impossibly muscled bodies. Has-beens and never-really-were celebrities dominate: ex-Seattle Seahawks linebacker Brian Bosworth’s dubious oeuvre is represented, while David Carradine enjoys a third comeback. More familiar faces turn up, though they aren’t immediately recognizable. Keanu Reeves isn’t as beautifully angular as he is in the Matrix, but he looks a sight better than Michelin-Man-muscled Lou “La Bamba” Diamond Phillips, or Kurt Russell, who resembles a lumpier Steven Seagal.

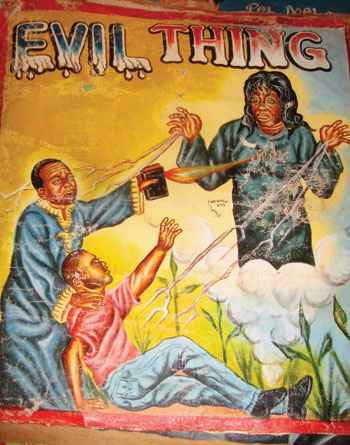

It’s the posters showcasing Nigerian movies that batter the brain. Heads are split open like casaba melons. The clash between Christianity and the Yorùbá religion is a common theme. Insanely portrayed through battles between preachermen and glowering demon people, both sides hurl lightning bolts, flames and other unidentified energy beams from their hands and eyes. In a memorable poster for the film Evil Thing, the Good Book becomes a flamethrower, scorching a cloud-riding succubus. Others dabble in, frankly, shocking stereotypes. Humans are parboiled in iron pots (Secret Adventure); headhunters sternly display their trophies (No More War 2); and cannibalism, cannibalism, cannibalism! The poster for Eaten Alive shows a flesh-noshing scene I couldn’t begin to describe in a family newspaper, though Joffe comments that he finds it “so grotesque, it’s comical.”

He has a point, but good Lord, where would you hang it?

Produced by professional sign-makers, the men who turned out the posters did so less for self-expression than to make a living. Most are signed, but only with the shop names: Puff Art, Mr. Brew Art, Blank Art and Surprise Art Services. In our digital world the posters hearken back to the good old days of hand-lettered and painted sign work. Historically, the nearest American approximation might be circus posters of the days of yore, advertising glass-eating geeks.

Compared to the original American advertisements, these posters don’t possess the cool, green-tinged menace of Steve Frankfurt’s designs for Rosemary’s Baby or Alien, or the jagged spookiness of Saul Bass’s posters for Psycho and The Shining. Ancestrally, they’re closer to Karoly Grosz’s work for Universal, including his posters for The Mummy and Frankenstein — though they can’t touch that particular master’s grasp of color, mood and composition. They mostly remind me of posters for Italian shockumentaries and mondo films of the ’60s and ’70s, or the slightly more palatable gialli films — gruesome horror flicks and murder mysteries featuring copious psychological torment and gouts of fake blood. If you have a strong stomach, look up the art for Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust. Better yet, don’t.

My internal art historian draws comparisons to the works of Ivan Albright and Joe Coleman, fine art purveyors of luridness and blood. I’d say only Mr. Brew, whoever he may be, took the extra step those artists took or take to unsettle the viewer. Overall, the posters are a counterpoint, if not a complimentary retort, to the many pretty things filling Primitive. The best are beautiful in their way, but it is a horrifying beauty.

In fairness, it’s the singularity of the posters that makes them seem more bizarre than they are.

Before entering Primitive, I strolled around the neighborhood, taking pictures to capture the area’s character. On a lamppost at Jefferson and Randolph, I found a plastered handbill showing President Obama, altered with a magic marker by a disgruntled passerby, who added horns and a goatee to the Commander in Chief. Nearby, I saw a giant severed hand, sans thumb, advertising the videogame gorefest Left 4 Dead 2. A short skip away, Johnny Depp, in phantasmagoric Mad Hatter apparel, advertises Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. Garish, violent and mind-blowing vistas, the only difference between these images and the Ghanaian posters is five-color printing and mass production. In multiplicity is normalcy, and in singularity art.

Based on a few more recent titles and Primitive employee Joe Rudy’s descriptions, the mobile cinema lives on in Ghana, albeit in reduced form. However, the need for oil-paint posters has fallen away, largely due to the availability of photocopiers. Computers, televisions and DVD players have reached further into Ghana as well.

Joffe laments their passing.

“This is a moment where art, ingenuity, and advertising meet in the crosshairs of history,” he said. “Met for a very brief period of time, and then it was over.”