Two-thirds of its population lives on less than a dollar a day, and yet Nigeria has the world’s second-largest film industry. It’s called Nollywood, and it provides Africa, and beyond, with a steady stream of action flicks and love stories.

For Dickson Iroegbu, the day he was almost killed by Nollywood began with an important decision. He could either say nothing and continue to look on as they made their trash films and shoveled money at each other, or he could put on a pinstriped suit and tell these Mafiosi that he wasn’t going to play their game anymore.

It was a Wednesday morning, and the sun was barely shining through the smog-covered skies over Lagos. The most important men in Nollywood, the filmmakers, were meeting near the National Theater to elect their president, when Iroegbu, 32, a filmmaker himself and winner of the African Movie Academy Award — Africa’s Oscar — rushed past the heavily armed police officers, took a deep breath and, with a loud voice, crashed the event.

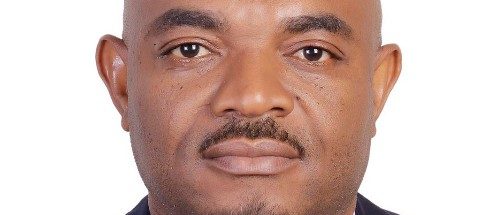

The invited guests, men and women, were standing in front of him in their sunglasses and suits, wielding their Blackberries. Iroegbu, a slight man with light-brown skin and glasses, grabbing and shaking their hands, said things like: “Let’s make Nollywood happen. We don’t need politics here. Why don’t you just get back to work? Enough with the greed, enough with the power games.” The filmmakers shook their heads, doing their best to ignore this man, a man they despised. Some said he should leave.

When Iroegbu did leave the event and got into his black SUV, he didn’t realize that someone had removed the bolts from the left front wheel. The wheel flew off while he was driving, and he was lucky to escape with nothing more than a few scratches on the car and a few scrapes on his forehead. He was also beaten up recently, says Iroegbu. “Welcome to wonderful Nollywood,” he adds.

Prostitution, Oil and Cannibals

Nollywood is the massive, pulsating film industry in Nigeria, which the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has declared the world’s second-largest film industry, after India’s Bollywood, based on the number of films produced. Shooting past Hollywood without the world noticing, Nollywood has made it to second place with films about family, love and honor, about AIDS, prostitution and oil, and about ghosts and cannibals.

In other words, films about Africa.

At least 900 films will be produced in Nigeria this year, twice as many as in Hollywood. Nollywood is a $200-million (€148-million) business in a country where 70 percent of the population still lives on less than $1 a day, where residents can consider themselves lucky if the power is on for two hours a day, and where raw sewage runs through open canals along the streets. It is a country known throughout the world for corruption, Internet fraud, prostitution and oil, but certainly not for its film culture.

Iroegbu is determined to change this. He wants to prevent corruption from taking hold of Nollywood and strangling it, as happens with almost all industries in Nigeria. He wants to make Nollywood visible to the rest of the world by promoting quality and creativity.

Iroegbu wants to win an Oscar for his country. That’s the plan.

The center of Nollywood lies in the narrow streets crisscrossing the Alaba market in downtown Lagos. The streets are lined with hundreds of small shops, the ground is muddy and tattered posters for love and action films hang between decaying buildings. The men and women portrayed on the posters are heavily made-up and wear animal skins over their shoulders. The generators hum while the vendors hawk their wares. In the Alaba market, the films that filmmakers like Iroegbu produce every year are burned, packaged and distributed.

Part 2: Low-Budget Flicks

Martin Onyemaobi is one of the kings of this world. His office in Alaba isn’t a real office, but more of a tiny storage room, filled with unpackaged DVDs, stacked in packs of 100, held together with rubber bands. Onyemaobi explains how the business works and reaches for his calculator. “This is where the life of a Nigerian film begins,” he says, “here, with this calculator.”

The average Nollywood film costs $20,000 to make. The average Hollywood production costs about $100 million. “I read a script,” says Onyemaobi, “and if I like it, I start calculating.” He is wearing silvery trousers and a silvery shirt, and a golden crown adorns his business card. Onyemaobi has already financed 50 films, which he has then marketed from his small shop.

Government film subsidies are almost nonexistent in Nigeria, and if there are any subsidies, most people assume that the money never leaves the pockets of those at the top echelons of industry unions. At first, Onyemaobi borrowed money from banks and private business people, but now, he says, he has enough capital of his own. He sells up to 300,000 DVDs or videos of a single film, at 250 Naira (€1.20) apiece. “I fork out money, hire a producer and off we go,” he says. His current hit, “Royal War,” set among the Yoruba people, is about a girl who is supposed to be married to the Yoruba king. “50,000 copies sold in the first six months,” says Onyemaobi.

Marketers like Onyemaobi produce up to 20 films a year, on paltry budgets upwards of €6,000. The films are shot with a single camera, usually in about a week’s time, complete with ketchup blood, ghost tricks and low-quality computer animation. Onyemaobi leans back in his chair. The air in the room is oppressive, it smells of mud and sewage and the plaster is peeling from the walls. But none of this seems to trouble Onyemaobi, who folds his hands over his stomach and says: “I’m currently making five movies at the same time.”

Gruelling Filming Sessions

Africa is a gigantic market, with 150 million people living in Nigeria alone. Nigerian films are exported to other African countries, like Ghana, Sierra Leone and South Africa, but also to the United States and England, and to Germany, where they are sold in African shops — in other words, to places where they can capitalize on the nostalgia of a large African Diaspora.

A typical Nollywood film takes place in a living room. Living rooms are good. Anyone who has a living room in this country has achieved a certain level of success. When Nigerians think of prosperity, they think of glass tables, flat-screen TVs, colorful sectionals and rooms like the one in which the film “Close Shave” is currently being shot.

It’s late in the afternoon and the actresses are exhausted. They seem distracted and are constantly having to repeat their scenes. Perhaps it’s because they have been working for seven hours without interruption, with no time to eat or drink, or even to sit down.

Or perhaps it’s because someone runs across the set every five minutes, a mobile phone rings or the generator breaks down. Or because the boy who is supposed to hold the microphone falls asleep and the crew gets drunk on Guinness and whisky during the shoot.

The story is about three aspiring female musicians who fall into the clutches of a female pimp. Power, the hope of prosperity, prostitution: These are popular subjects in Nigeria, subjects that stir the nation.

Part 3: Giving Nigerians a Voice

Nollywood’s success began in 1992, with the film “Living in Bondage.” At the time, after years of recurring military coups, someone finally had the courage to address the subjects that related to ordinary people. The film is about a man who falls under the influence of a religious cult, and about money and black magic. At the same time, the film also suggests that the new wealth in Nigeria is the result of demonic practices — and the source of inequality in the country and the suffering of too many people. “Living in Bondage” was liberating for people in Nigeria, because it meant that suddenly they had a voice. Hardly anyone in Nigeria today isn’t familiar with the film.

Instead of showing their film in expensive cinemas, the producers distributed it as a so-called home video, which gave them access to a completely new market. Suddenly families could hold film evenings, with entire neighborhoods gathering around a single television set as if it were a campfire.

At its height, shortly after the end of the military dictatorship in 1999, Nollywood was flooding the African market with up to 2,000 films a year, and Surulere, the nightlife district in Lagos, became its creative center.

The road to Surulere leads down a four-lane highway exit, from which traffic is dispersed into smaller streets. A cacophony of car hors, shouting and failing engines fills the air. Surulere is a loud, Dionysian place, where actors, costume designers and screenwriters live, work and party. It’s a place where actors are cast, a place to see and be seen — and a street known as Winnies is something of a stage for it all.

Winnies was originally a simple guesthouse, a hangout for actors and filmmakers in the early days of Nollywood. Now the place is so popular that the entire street is called Winnies. Casting notices are pinned to the walls, specifying what the directors are looking for: “If you are fat, tall and speak various Nigerian languages fluently, call us. We are looking for a film production.” Or: “Huge simultaneous casting call for 9 films.”

Actors as Day Laborers

The street is narrow and the air smells of a mixture of exhaust fumes and the strawberry perfume of young actresses standing on the sidewalk, waiting to be discovered — like young Victoria. Every morning, the young actors who hope to become famous stand in front of Winnies, like day laborers, waiting to be taken to the sets on the location buses of film producers like Mr. Divine.

He is standing in the guarded parking lot of a hotel, as a minibus reels toward him, swerving to avoid the potholes. The bus is rusty, dented and covered with colorful film posters. Divine steps to the side. “The show goes on,” he says. “We don’t have any time.”

The bus is a Mercedes, but for Divine it’s much more than that. “What’s inside that bus is Nollywood,” he says, “my entire film, everything inside that thing.” The thing slows down and comes to a stop next to him, and then his film squeezes itself out through a sliding door: 15 young actors and assistants, loaded onto the bus at Winnies and booked for two weeks. It also contains an HD camera, a cameraman, a director, two plastic bowls filled with cassava porridge and spicy chicken, three lights, a microphone, an Adidas bag full of costumes, a few bottles of Guinness and the generator. And three stars. “It all comes to $38,000,” says Mr. Divine, pointing out that that’s the trick, “making films with next to nothing.”

Mr. Divine, the head of Divine Touch Productions Limited, has a real name: Emeka Ejofor. Stage names are good for business. The film he is currently shooting will be called “Strippers.” It’s about three young women and a suitcase full of money. The actresses are wearing very high heels and very little clothing, their fingernails are as long as colorful as candy canes, and they seem drunk — and maybe they are drunk.

‘Nollywood in Crisis’

The film will look like all Nollywood films. Seen through the eyes of Nigerians, it will be glamorous, exciting and well-acted. Seen through the eyes of the West, it’ll be trashy but charming, and somehow unintentionally funny. The film will be a big seller, because there will be many stars on the cover. It will remain unknown beyond Africa’s borders.

Dickson Iroegbu, the filmmaker, also has his office in Surulere. It is the day after his car was rigged to crash, and his two mobile phones are ringing every five minutes. The callers want to know what he was thinking, crashing the filmmakers’ event the day before. Iroegbu, normally a quiet, polite man, becomes agitated and raises his voice. “Nollywood is in a crisis,” he shouts into his phone. “It can’t go on like this.”

He takes a sip from a glass of red wine, even though it’s only noon. A gold-framed portrait of Martin Luther King hangs on the wall above his desk, next to a picture of US President Barack Obama. The prizes he has already won with his films are displayed on a cabinet. Iroegbu has been in the business for a long time. He was a teenager when he wrote his first screenplay.

Next to the oil industry, Nollywood is the second-largest employer in Nigeria. It has its own stars and its own red carpets, even its own version of the Oscars: the African Movie Academy Awards. Hundreds of thousands of the home videos it produces are displayed on dealers’ shelves, in the form of VCDs and DVDs, and the films are also broadcast on television channels like Africa Magic. Hollywood films play almost no role at all in this country.

Iroegbu punches his fist into his left hand, and then he says that he has made a decision: “I won’t make another film until I’ve raised $2 million.” He says that he has a fantastic script, a project called “Child Soldier,” which twins a story about Africa with the story of a child soldier. Iroegbu dreams the dream of unexpected success, like the success enjoyed by the science fiction film “District 9,” a low budget project from South Africa, which was filmed in only two months, became a box-office hit in the United States and was even nominated for four Oscars this year.

Iroegbu says that he knows that he has made enemies with his idea. He also knows that they will still try to sabotage his car and ambush him at night. “It makes me afraid,” he says, but he adds that it’s worth it, because he hopes to win an Oscar for Nollywood with his film.

“If all goes well,” he says, “my film will be a ‘Slumdog Millionaire’.”

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan