Distribution key to Nigeria’s burgeoning film movement

It’s been nearly two decades since the current incarnation of Nigerian filmmaking — Nollywood, as it has come to be known — took Africa by storm.

From the seaside metropolis of Lagos to the chop bars of Accra, Nigerian film has steadily become a surprisingly viable industry built from the ground up by enthusiastic locals working with little money and few resources.

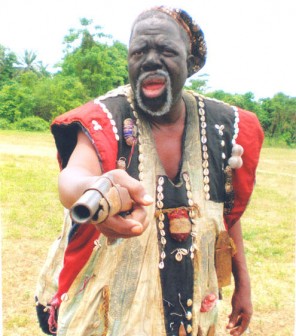

These vibrant, homegrown dramas — often gritty tales of witchcraft and the occult, or wish-fulfillment fantasies about get-rich-quick schemes — remain extremely popular with a viewing public eager to escape the day-to-day reality of a country still wrestling with extreme poverty, widespread corruption and shaky-yet-improving infrastructure.

A lot has changed since 1992, when Ken Nnebue’s “Living in Bondage” — widely considered the forerunner to today’s Nollywood — hit the streets, selling an estimated 750,000 videocassettes and igniting a do-it-yourself film movement that relies on an informal network of DVD distributors.

Despite advances in both technology and storytelling, Nollywood now finds itself at a crossroads: In order to take the next step in its evolution — an ambition passionately advocated by many in the industry — insiders say theatrical distribution is the next logical step.

But can it actually happen?

If a group of roughly 70 local artists and filmmakers have their way the answer is an unqualified yes. The goal of the group, which has incorporated as a company called FameCorp., is to transform the industry by creating the infrastructure necessary to ensure local films will be screened in theaters before their release on VCD and DVD.

“FameCorp., is intending to build in each state capital a complex with a cinema hall, a multi-purpose hall for concerts and a warehouse for CD/DVD and music magazine distribution,” says its chairman Tee Mac Omatshola Iseli, who adds that FameCorp’s members have pooled their resources and plan to have an initial public offering of some of its stock by the end of the year.

It’s not as if Nigeria has never had a viable theatrical distribution circuit.

“In Nigeria, we have had a long-running romance with theatrical distribution of both Nigerian and foreign films, especially Indian films, which remain quite strong in certain parts of the country,” says Emeka Mba, chairman of the National Film & Video Censors Board (NFVCB). “Filmmakers like Eddie Ugboma, Ladi Ladebo, Dr. Ola Balogun and late Herbert Ogunde all made films on celluloid that were commercially successful and distributed to cinemas in Nigeria.”

Indeed, Ogunde’s classics “Aiye” and “Jaiyesimi” were bonafide hits when released in Nigerian theaters, even though they were in Yoruba and not the official English language.

“Cinemas are no aliens to Nigerians,” adds director Izu Ojukwu, whose upcoming drama “The Child” will receive a theatrical release in Nigeria. “As a mater of fact the southwest and core northern Nigerians already have a very strong cinema culture going as far as the 70s. Nigerians love entertainment — even my grandma in the village would love to watch movies on the big screen. Evidently, only a few can afford it. Nevertheless, I believe that eventually we will be living our theatrical dreams.”

Currently, there are 50 screens in Nigeria, primarily in the capital city of Abuja, as well as Lagos and Port Harcourt, an oil hub in the south. The FameCorp. goal to build 36 new theaters — one for each state — is coupled with an attempt to ensure that moviegoers pay a reasonable price for a ticket.

“The few existing cinemas in Nigeria are visited by the elite as cinema tickets of N1,500 ($10.00) are too expensive for 70% of the population that is still living below one dollar a day,” says Sandra Mbanefo Obiago, a Lagos-based producer whose Communicating For Change film company produced the Nollywood trilogy “Too Young, Too Far, Too Late.” “By addressing the lack of cinema infrastructure in Africa’s most populated country with a 150 million population eager to become regular theatergoers, FameCorp’s model — ‘local entertainment centers’ — is sure to draw huge crowds.”

While that may be true, widespread piracy is a major hurdle since VCDs and DVDs can be copied and distributed with ease. In an effort to clamp down, Nigeria’s government, led by Mba and the film board, recently launched a new film distribution framework mandating that all film distributors be officially registered and regularly report on their distribution figures.

Still, according to Obiago, the situation isn’t going to change overnight. “This is being strongly opposed by the powerful market traders who control Nollywood distribution business both locally and internationally,” she says.

There are glimmers of hope, however, that locals will indeed pay to see quality films in theaters. Last year, when director Kunle Afolayan released his thriller “The Figurine” in three local multiplexes, the film ended up beating Hollywood fare at the boxoffice, according to the NFVCB.

Afolayan, who recently won a host of African Academy Awards for “The Figurine,” including best picture and best Nigerian film, says the time has come for Nollywood to think bigger than the local market.

“Nigeria definitely needs more theatrical distribution, not only within the country but also on other continents,” he says. “We are beginning to make films that the rest of the world can relate to. Quite a number of people are back to shooting on celluloid and HD and telling our own stories with good production values.”

FameCorp.’s Iseli agrees, adding that Nollywood filmmakers should not shy away from larger productions that could attract global audiences. To that end, FameCorp. has already begun seeking interest in a large scale bio-pic of Mary Slessor, an 18th century Scottish missionary who repeatedly ventured into the Nigerian hinterland when the eastern areas were dubbed the ‘White Man’s Grave.’

Rob Aft, the head of Compliance Consulting who closely monitors the Nigerian film industry, says that while Nollywood films have improved recently, local filmmakers must continue to make a commitment to high production values if their work is to be taken seriously beyond Nigeria’s borders.

“The acting has improved, the scripts are better and the equipment they’re using is first rate,” he says. “Nigerian films must be of sufficient quality to screen in real movie theaters and at international film festivals if they are to grow outside their current markets. Clearly some of their films have reached this threshold and their success should inspire other filmmakers to raise their standards — and they’ve done it without sacrificing the energy and originality that are at the core of the Nigerian film industry’s success.”

Afolayan adds that his work and that of his fellow filmmakers shooting on celluloid “should be given the chance of touring available cinemas all over the world.”

But before that can happen, the insiders agree it’s time for Nigerians to be able to watch movies as they were intended — on the big screen, with the lights dimmed.

“There is no example anywhere in the world where anyone would find a sustainable film industry without theatrical distribution being part of it,” Mba says. “In fact the very concept of cinema and film is anchored firmly on the concept of theatrical distribution. Without it, the long-term survival of any kind of film industry would be jeopardized.”