In Africa, typecasting gets turned on its head. In Nigeria, white people get the bit parts, playing robbery victims and “the third guy on the left.” Part 3 of 5.

My first acting role in Nollywood behind me, I looked forward to gaining more experience and, with any luck, acting in a larger-budget Nigerian film. Eventually, I get a call from a director who wants me to play the victim of a robbery, a classic white-man role. I don’t want to contribute to the perpetuation of this humiliating stereotype, but it is an opportunity to see another Nigerian movie getting made, so I agree to do it.

The set for the day is a dingy hotel tucked behind a bustling market. Before shooting, I sneak out and wander among booths slapped together with bent wood and rusty tin slats. There is a booth for everything: jackets and shoes, office supplies, mattresses, padlocks, scarves and dresses, and beautifully arranged fruit of every shape and color. I settle on a single fried plantain, served hot and covered in ash, which costs about 40 cents. It’s delicious.

The actors mingle in the hotel lobby and compare their self-supplied wardrobes. My dingy T-shirt is not appropriate garb for a wealthy man about to get robbed, so we look around at the various cast and crew and find a young man of about my build. He has three shirts, two slick silk jobs and one worn, plaid one. I get the plaid.

After a surprisingly short delay (only two hours!) the crew is ready to shoot the robbery scene. I have a borrowed briefcase, but Earnest, one of the three actors who are to rob me, can’t find a knife. He wants something realistic for the scene, something menacing enough to scare a grown white man in Africa into turning out his pockets.

I assure him that I’d give up my own grandmother in the face of little more than a convincingly brandished butter knife, but he is determined. Eventually he gains entry into the hotel kitchen and finds a massive butcher knife. When I see it, I suggest we rehearse the attack scene a few times so as to avoid any errant, injurious movements. “No, I’ve done this kind of scene many times,” he says. “Don’t worry, we’ll just go with it.” There is no time to argue as the director hurries us into the alley and calls “Action.”

I stroll down the alley beneath curious hotel guests peering down from their windows, none of us sure what is about to happen. The three thieves come from behind and wrench the briefcase from my hands. One throws me down to the concrete, hard. I wince and try to get up, but then there is a knife at my throat. Not above my throat or near my throat, but at my throat. My fear is suddenly very real, just in time for the cameraman to come in for a close-up. After the thieves run off I jump up and begin yelling about my stolen money. I wait for the director to call “Cut,” but he doesn’t. So I improvise a few lines about how important the money is and how sad I feel, then I too run off camera. We do three shots, each with the same quick, startling progression, each a little too real. Method acting has reached West Africa.

A few days later, another role comes up. This one in a pilot episode of a soap opera that, according to the producer, is to be the Nollywood version of Friends. I am brought in to play a white guy who has recently moved to the main character’s neighborhood. There is the possibility of a recurring role, so I am particularly excited on the first day of shooting.

The production company office is empty when I arrive. I knock on a few doors, but no one is there. Back outside, I find the director on his cell phone, frantically calling all the actors who are supposed to already be shooting scenes. He sees me and apologizes, but says that I will have to wait a few minutes for the actors in my scene to show up. Minutes turn into hours, and the necessary cast members do not assemble until well into the afternoon, at which point the director sits everyone down for a lecture on how to behave properly in a professional setting. One by one he admonishes them for their tardiness. I sit in a corner, comfortable knowing that I had been on time. But then he is speaking to me.

“Isn’t that right, William?”

“Isn’t what right?”

“A professional actor does not chew gum during a meeting,” he says. Everyone is looking at me. “Is that how they do it in America? Do the famous actors sit there chomping on a piece of gum while the director speaks?”

“Um, I really wouldn’t –”

“No, they don’t,” he says. My face and neck are very hot all of the sudden, and I hang my head, trying not to move my jaw.

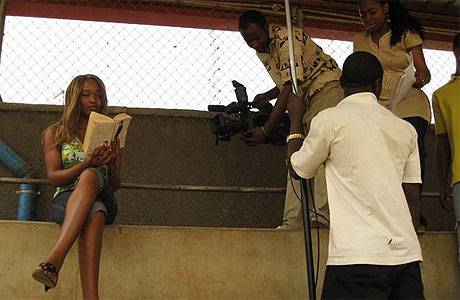

Admonishments done with, we all walk to a local soccer stadium to shoot a few scenes. Within minutes a guard appears and kicks us out for not having permission to film there. Then it’s on to a grocery store, its aisles crowded with shoppers just out from work. Two shots take three hours. Finally it is time for my scene, set in a tacky gift shop whose owner is ready to close.

Two actresses are to spot me as the potentially wealthy new neighbor and chat me up. I am supposed to become indignant and unleash a self-righteous diatribe about the money-grubbing proclivities of Nigerian women, then storm out of the store. Despite the questionable merit of the writing, I am thrilled to be able to test out my acting chops. My last meaty role had been in a poorly attended college production of a Steve Martin play.

The thirteen hours of waiting are finally over. The scene begins, and the first actress gets one line off. Then the power goes out.

Outside on the street, the actors and crew laugh and pass around bottles of spiked pineapple juice. No one seems frustrated. Even the director is smiling and sipping a drink. They are used to the delays, the frustrations, the prickling heat. I stand to the side, upset that the whole miserable day had come to nothing. I realize that if I am going to make it in Nollywood, I have to adapt. So I take a deep breath and rejoin the group. They pass me a bottle and I take a sip of the bitter drink, then press the cool bottle to my forehead.