This particular study of King Wasiu Ayinde’s pattern of songs and musical art has provided structure and metaphor for creating an imaginative world peculiar to human development. In this report, Remi Aderibigbe takes a look at the structure of Wasiu Ayinde’s style of music with special focus on his art of oral traditions.

Speaking on the oral composition, an historical appraisal, one of Nigeria’s distinguished literati gurus, Dr. Dandatti Abdulkadir, argued that everybody can compose a song, it is prerogative neither of the old or the young, but the only difference lies in specialization and professionalism. Therefore, the essence of oral formulaic technique as advanced by the scholar is to understand materials originally composed orally by Wasiu Ayinde, a fuji icon.

When King Wasiu Ayinde came out with the album titled, “Talazoo Fuji,” in 1982, many people were oblivious of the import of the track, Ori mi ma je n se won o, Eleda mi, ma je n se won,” which literally means “may God protect me from the evils of the wicked soul.” It was not until he turned to the cynosure of the members of public through his kind of music that thousands of music lovers and analysts began to regard him as a serious fuji musician of our time.

Consider for instance, “Awa te n wi ree o, Awa te n wi ree oo, Ayinde Wasiu mi, Ayinde Wasiu mi;” meaning, “We are the one, We are the people, Ayinde Wasiu is the group.”

There is shorter and concise rhythmic pattern which he regularly employs under the same metric conditions to express a given essential idea. The conclusion to be drawn from the above lyric is that Ayinde is a composer with proper identity.

In narration pattern and analytical methodology designed with philosophical approach, Wasiu Ayinde has always been a custodian of rhythmic phraseology in relation to the social environment. Take for instance, “Osi palaba si pabo pabo, Ole wase se, Ole to ba wa nitosi, Tete wase se,” meaning, “The lazy ones, Find a job to do, The lazy ones, Be engaged with any profitable venture.”

The stylistic coloration and emotional impact employed here is a high power imagination and expression of a particular thought. The artiste, probably speaking from Lagos experience, is trying to chastise some who derived joy in wandering rather than be engaged in order to guarantee their genuine source of livelihood.

To appreciate Ayinde’s skill on the artistic strategy and narrative device of structural analysis oral perspectives, let us examine critically the syllabic pattern associated the songs like: “Awa de ba ti n de o, Awa de ba ti n de o, Awa momo de bi a ti n de o, Awa tun ti de bi a ti n de o, Dr. Omogbolahan ma korin to fogbo yo,” and “Bo ti se wumi ni n o, Bo ti se wumi ni n o ko, Fuji tote yii o.” This is simply means, “We are at it again, we are back to the business.”

This aspect of music captures the mood of the singer in different style of oral composition and memorization.

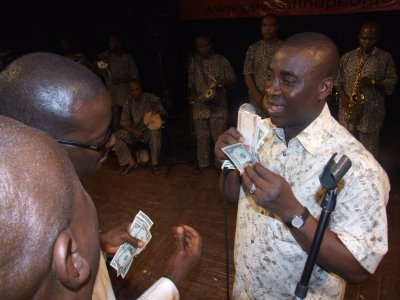

In an encounter with Ayinde on stage at Ijebu Igbo, Ogun State, it was discovered that the leader of Talazoo fuji organization often employs strategies of satire in sing praising people.

In composition like, “Mo ti so tele tele k’an to ma wu, Mo ti so tele tele k’an to maa sako, Iro ni pepe n pa, Aja lo leru,” in which he tries to express his foreknowledge and superiority to his rivals.

This particular composition is identified with linguistic style and proverbial appraisal, which I noticed at that moment coupled with his facial expression, costumes by his band boys incessant gestures, eye contact and of course, improvisation of his music.

Let us consider another compositional pattern of song by Ayinde. “Ma gbe tana kuro lara, Sogologo ban n g’ose, Ijo, Ijo, Ere Ere, Ma gbe t’ana kuro lara, S’oko l’ogo ban g’ose.”

One would examine parallelism of thought, symmetrical thought, phonological style, grammatical methodology and synonymous words, which are applied to oral art.

It is no longer new to hear that fuji genre of music in Nigeria belongs exclusively to a religious group since it metamorphosed from were kind of music to ajisari and now to modern fuji as echoed by Ayinde in this words: “Eyi o ni modern fuji, Eyi o ni modern fuji.”

If the art of composing Yoruba oral poetry consists of selection and discrimination of verbal materials, Wasiu Ayinde’s form of music can be described as an epitome of knowledge and symbolism, whose style of diaphonic word is of great hedonistic values.