Want to become a Nollywood star? Here are the three lessons you’ll need to learn before you seek fame on the other side of the world. Part 4 of 5.

This is the fourth part in a five-part look inside “Nollywood,” the Nigerian film industry.

*****

My bid to make it in Nollywood is gaining steam, but I need to hone my skills and learn from seasoned veterans, so I arrange to observe an audition. It takes place in the shadow of the National Theater, a spaceship-like structure visible from miles away, the only landmark in an otherwise desolate, dirty swamp bisecting the two main sections of Lagos.

Behind the theater in a dusty square, actors, dancers and other industry players regularly gather for auditions and meetings. A grove of trees to one side of the square marks the actors’ area, and a tiny open-air pool hall to the other side marks the dancers’ area. In between are the offices of the Actors Guild of Nigeria, and on the outskirts of the square are several “chop houses,” or restaurants, and a few bars.

Lesson One: Bow Your Head

Before today’s audition can begin, the actors gather under the canopy of a large tree for a group prayer. One of the veteran actors steps forward. “Welcome, everyone. Let us bow our heads in prayer.” He holds his arms outstretched over the heads of the others. “Please God, help us perform our best today. Destroy the agents that would delay our projects, O Lord. In the name of Jesus. Father, I ask that these agents be nullified in the name of Jesus. As you cover everything in the blood of Jesus, Lord, destroy our enemies who would have us not do well at this audition today…” He continues for some minutes before closing with a solemn “Amen.”

In Hollywood, a pre-audition prayer would likely be met one of two ways: with derision or a lawsuit. But the prayer is not unusual in a country as religious as Nigeria, split equally between Christians and Muslims, where mega-churches in the south draw tens of thousands of worshipers to weekly services, and where several northern cities practice sharia law. What is unusual is that I am standing next to a Muslim friend, and he has taken part in the Christian prayer along with everyone else. Later he will tell me that most of the directors in Nollywood are from one predominantly Christian ethnic group, so he uses his middle name instead of his Muslim-sounding first name and always takes part in the Christian prayers.

Lesson Two: Patience Is a Virtue

After the prayer, a producer announces that the casting directors cannot make it today, and the audition is postponed until further notice. The actors sigh and mumble to each other but no one seems particularly surprised. Once again I am reminded that in Nollywood, and in Nigeria in general, things never go as planned and patience is a requirement for survival, and for sanity.

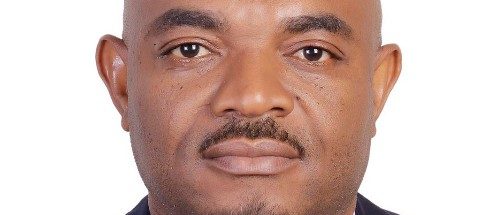

As we start to leave I notice a man in a bright yellow shirt, black shorts, black cowboy boots, and a black cowboy hat walking by. His name is Emma George. He is a small man with a thick beard and kind eyes. Though well into his forties, he has just recently moved to Lagos and has only been acting for three years.

“I was working at the Ministry of Transportation before, but I had a passion for acting,” he says. “My mother thought I was crazy and said, ‘Emma, are you sure? You’ve got a good job.’ And I told her, ‘Mama, I have to go for it.’” Because of his age, dark beard, and well, the black boots, Emma most often gets cast as the villain, though he would rather be seen as a leading man. “I played a loverboy only once, in Virginity of the Goddess. I’m a real gentle soul, but I’m always carrying a gun onscreen.”

Lesson Three: Turn the Other Cheek

I ask Emma about the frustrations of trying to make it in Nollywood: the unpredictable schedules, the meager pay, the shoddy production quality. He nods knowingly. “Acting in Nollywood is not an easy thing,” he says. “But with patience, perseverance, and determination, we’ll get there. Nollywood is still young compared to Hollywood, but we believe we’ll get there with time.”

Emma says good-bye and heads to a nearby restaurant, where he hopes he’ll be seen by a director or producer. As he leaves, I realize that he embodies the dominant trait of many Nigerians I’ve met. Here’s a middle-aged man who left his steady — if unprofitable — government job to pursue his love for acting and who stays positive despite numerous setbacks and dim prospects. That is Nigeria in a nutshell: millions of people streaming into the cities with few, if any contacts, looking for whatever work they can find and striving through all manner of obstacles. Whether investment banker or dressmaker or bread seller, they are among the most resilient people I’ve come across.

My attempt to observe an audition had failed, but there would be other chances. My friend says we should go. A quick wind picks up dust and whirls it across the now-empty square. Then a little girl in a ragged dress and pink sandals walks by holding a monkey on a chain. I look at my friend for an explanation but he just smiles, shrugs, and turns to leave. The little girl walks to the middle of the square and stops. The monkey sits down. I follow my friend back toward the main road and the teeming Lagos traffic. When I look back, the girl and the monkey are gone.