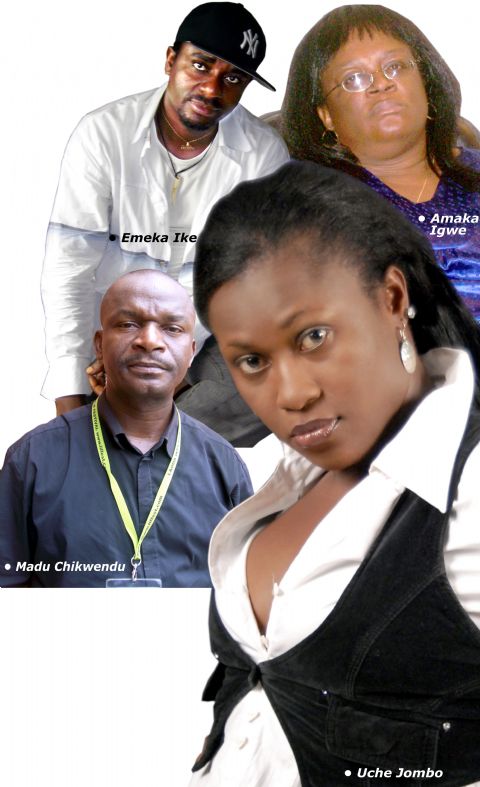

Black images stand out starkly against a white background, so sharp, so vivid, they seem to take on a life of their own.

And it’s not surprising, for these images, which show traditional African hairstyles that now seem to belong to a long lost era, were the life and soul of women of old to whom hairstyling was more an artistic and cultural expression than mere beauty enhancement.

Back then, there were no wigs, weave-ons, extensions and other Western forms of beauty and hair enhancers so beloved of the average Nigerian woman today.

All these women of the past had, were their nimble, creative fingers, rolls of black thread, combs and, of course, a headful of thick, kinky, black hair. Out of these sprung forth magically shaped, intricately woven and plaited hairdos that have captivated all who have beheld them and left many amazed at their sheer beauty and artistry.

These hairdos with exotic names like suku sinero, ito lozi, onile gogoro, among others, have also played a big role in the career of one of the country’s topmost photographers and documentarists, J.D Okhai Ojeikere.

As an up-coming photographer with an artistic bent back in the 1950s, the young Ojeikere had been fascinated by the different traditional hairstyles of Nigerian women. He saw the stylish shapes and unique designs as a form of art; and the women who created such ‘head wonders,’ as artists.

However, fashion is fickle and new styles come and go with dizzying regularity. It was not long before these wonderful ethnic creations, which were a reflection of the people’s culture, gave way to something entirely new and alien: wigs.

Vanishing culture

“Suddenly these styles disappeared and the women started wearing wigs,” said Ojeikere, ace cameraman of over 50-years’ standing. “I felt bad that I did not take their pictures when they were plaiting their hair.” Then in the mid-60s, the women went back to their first love-hair plaiting-and the observant photographer, not wanting to miss this golden opportunity, took up his camera and went to work.

“When they started plaiting their hair again, I said I had to take their pictures before they changed their hairstyles to something else again. Maybe this time, it won’t be wigs but they will be shaving their hair! Getting the women to pose for me was not a problem. I used friends, relations, neighbours and the general public. If I see you with a good hairstyle or headgear, I will approach you and if you are willing, I will take you to the studio and take your pictures.”

The result of this ground-breaking work-capturing the hairstyles on film for posterity-are enduring images of immense artistic beauty, grace and style.

They have graced many exhibitions locally and internationally, and have become the subject of heated debates at seminars, symposia and even in scholarly and intellectual circles. Ojeikere’s work has taken him to places including: Spain, Germany, United States, France, Belgium, South Africa, and Japan.

He recalls the overwhelming responses to the images in all those countries, but notes that the kind of questions he was asked betrayed their ignorance about Nigeria, especially in relation to culture and tradition.

“In Geneva, for instance, representatives of 26 schools who came for a seminar which I anchored, were asking me questions like: “What was happening in Nigeria that everybody got crazy about plaiting their hair? And I told them that nothing happened, that it was just our way of life, part of our culture and heritage, that it was no big deal.

It was nothing special to our women; it was just their style. They were asking whether they put sticks or pieces of iron in the hair that makes the hair stand like that. And also how long it takes to make and how long it lasts. It just showed their ignorance about Nigeria, that they don’t know anything about the country. But they were amazed at the hairstyles and they appreciated them.”

To him, “All these hairstyles are ephemeral and I want my photographs to be memorable traces of them.”

Youthful passion

Ojeikere’s passion for his craft began as a young man of 19 when he acquired his first camera by chance, a Brownie D model which he bought for two pounds in 1950.

With no formal training in photography except for some advice he got from a neighbour in Abakaliki where he lived, Ojeikere began taking pictures and developing films. Back then, photography in Nigeria was still in its rudimentary stage and as a profession was relatively unknown.

His elder sister even tried to dissuade him from his chosen path, advising him to train as a carpenter or bricklayer instead of what she called, ‘this lazy man’s work’.

But he persisted. “The very first pictures I took, I charged six pence per shot. Since that day I [first] handled a camera up till now, photography has not been a disappointment to me. I have been living off photography since that first day. And I knew even back then that I was going to be a successful photographer. I had that confidence in myself.”

After working for himself for three years, Ojeikere got a job as a darkroom assistant at the Ministry of Information in Ibadan in 1954.

He soon got bored with the routine nature of the job, and longed for something more challenging. He moved to the first TV station in Africa, WNTV Ibadan, where he worked directly under the late, great musician, Steve Rhodes, then the Director of Programmes. “He was a wonderful man. He was very vast and knew everything,” Ojeikere reminisced about Rhodes.

After three years at the station, the photographer joined West African Publicity, Lagos (now Lintas). He was there for 12 years, retiring in 1975 to go into private practice.

Though time and age have slowed the veteran down a bit (he will be 80 next year), the Edo-born Ojeikere is still active in his field. “I still take pictures. In 2007, I was at the Abuja Carnival to take cultural pictures.

But I didn’t go last year because it doesn’t make sense at my age to continue taking pictures when the ones I have taken have not been filed. I also keep busy by arranging and filing my negatives.”

Recording moments of beauty

So how fulfilling has his career choice been? “It’s been fulfilling,” he maintained. “Nothing regrettable at all. If I had to come back even three times, I will return as a photographer.

I have always told the younger ones to always have patience and not be in a hurry; I wrote applications for three years to the Ministry before I was employed. None of these young people would do that.

They will give up. So, have patience, be focused and very dedicated to their profession, and any picture they take, they should always keep the negative. I always do that. You can see my negatives from the 50s.”

While he is impressed with the new technology in photography, Ojeikere is less keen on the effect on photographers. As he pointed out, “It makes people think less because whatever you do, you use the computer to manipulate, so it’s not your own idea.

When we started, we were taking pictures and developing the films ourselves. Now, you take pictures and take the film to the lab for developing; you have not made full contribution. All you did was take the picture and any stupid person can do that. There’s no more creativity. It makes photographers lazy and less creative.”

In closing, Ojeikere was emphatic that: “Creativity is inborn. It’s a gift. It’s not something one can force. I have always wanted to record moments of beauty, moments of knowledge. Art is life. Without art, life will be frozen.”