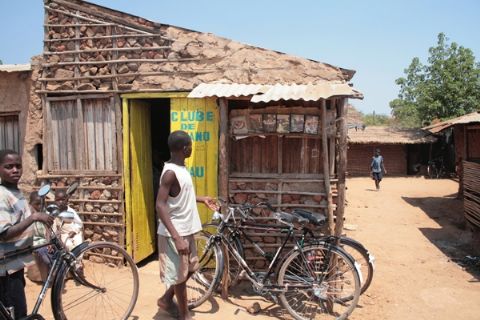

Surround sound, it’s not. But a bamboo-and-mud hut is all it takes to draw film audiences ready for entertainment at 40 cents a ticket

Soon after the sun rises over the rolling hills of banana trees, Paulo Manuel Caetano leaves his grandfather’s mud-walled house and walks straight toward the center of town.

He passes the vegetable sellers piling tomatoes and avocados on handmade reed mats, and the women carrying buckets of corn kernels on their heads toward the mill. He walks by other barefoot teenagers making their way to the dusty soccer field across the only paved road in town. And then, not far from the informal traders setting up their stalls of plastic sandals and tissue paper, he stops at a bamboo-and-mud walled hut and surveys his options for the day:

“Phantom Soldiers,” “Shadow Fury,” or, here in Portuguese-speaking Mozambique, Matt Damon in “A Identidade Bourne.”

Mr. Caetano approves. “I like the ones with fighting,” he says. “I get here very early in the morning to find a movie.” And with that, he pays the equivalent of about 40 cents to Santos Fernando Casão, the gatekeeper, and ducks into the cinema – a sweaty-smelling room with six wooden benches, a dirt floor, an old Supra television set, and lots of teenage boys.

Movies are popular here. This town, the center of a sweeping district of about 95,000 people, mostly subsistence farmers, boasts more than 20 small cinemas – a figure that might surprise an outsider looking at the mud huts and goats wandering around, but one that seems normal to locals, and unsurprising to film experts.

“They’re all over,” says Russell Southwood of the movie houses. He is the chief executive of Balancing Act, a research and consulting firm focused on Internet, broadcast, and audiovisual media in Africa, and has written about the phenomenon. “With pirated videos, they have effectively replaced cinemas.”

The film industry is booming here. Many countries in Africa have produced critically acclaimed films, including South Africa’s Oscar-winning “Tsotsi,” and most host at least one regional film festival. Nollywood, the low budget, soap-opera-style movie genre from Nigeria, has also exploded in popularity.

Movie venues, however, are still few and far between. Like Gorongosa, much of the continent is just too poor and too remote to have its own Cineplex.

“Getting prints across the continent is hugely difficult,” says Lara Preston, the producer of the Africa On Screen Film Festival. “The big studios won’t ship digital prints because of pirating – they want to ship reels. And that’s hugely expensive.”

Some film groups and nonprofits have started using mobile movie theaters to reach the viewers. This style of movie showing, which was common decades ago in the rural United States, is also popular in other developing regions. The Eighth International Indigenous Film and Video Festival held in Oaxaca, Mexico, for instance, used mobile theaters to bring entry films to the region’s remote villages. In Africa, groups such as the Zimbabwe-based International Video Fair Trust will travel around the region screening films on a variety of social topics, from HIV/AIDS to domestic violence to microfinance.

“Our biggest audiences are in the rural communities. Our average sized audience has been anywhere from 50 to 500,” says Charity Maruta, of Zimbabwe’s International Video Fair Trust.

But most common here are the small theaters like Mr. Casão’s. The style might vary a bit place to place. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, a DJ will often mix a new music score and provide a sort of informal simultaneous translation of the actors’ lines. But they usually have the same basic setup: a room, an entertainment system, and a bunch of pirated videos.

Action and kung fu movies are the most popular, says Casão, gesturing to the wall where movie jackets are displayed to draw customers.

He picks out the features himself, he says, in the informal markets of Beira, the country’s second-largest city. Every few weeks, he explains, he makes the five-hour minibus taxi journey there and browses the piles of pirated DVDs, which are either imported from either China or somewhere else on the continent. (Preston says there are more than 1,000 factories in Nigeria churning out pirated movies. “It’s a massive, massive problem,” she says.)

For about 80 meticais, or just over $3, Casão can buy a film of his choosing. For about half that amount he can pick up an African music video, which he plays in between the features.

“It’s worth it,” Casão says. “During one day we make 350 meticais.”

All day, Casão collects money from customers like Caetano and makes sure the films keep running. People come and go during the films, and will sometimes dance along with the music videos. Today, a group of elementary school children are grooving outside the cinema in the red dust as the sounds of Salsicha, a hip-hop style Angolan music star, come pumping through the bamboo walls.

In Tanzania and Uganda, entrepreneurs have started buying up the small movie houses to make their own informal theater chains. But in Mozambique most of the cinemas are independently owned. Casão works for an owner who has two theaters in Gorongosa; a block toward the market, Louisa Luis lies in the shade next to her cinema, which she’s owned since 1999.

Ms. Luis was one of the first cinema owners in town. She had been selling corn, but saved up enough money to buy a television and amplifying sound box. She bought a piece of land near the central market, and then built a cinema large enough to hold about two dozen viewers. She has replaced her DVD player once, she says, but still has the same television. And business is consistently strong.

“Everyone comes to see movies,” she says. “Young people, old people.”

She is open from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., and is full all day. Admission is 10 meticais, but if you want to stay for a double or triple feature, she says, you have to pay for each.

Like Casão, she specializes in Western-style action movies, and goes twice a month to Beira to pick out the DVDs.

“Karate, boxing, kung fu, war,” she says as she watches a group of three young men duck into the cinema. “You know, they like action.”

And her own preference?

“I don’t like to watch the movies,” she says. “I’m tired of them.”

By Stephanie Hanes