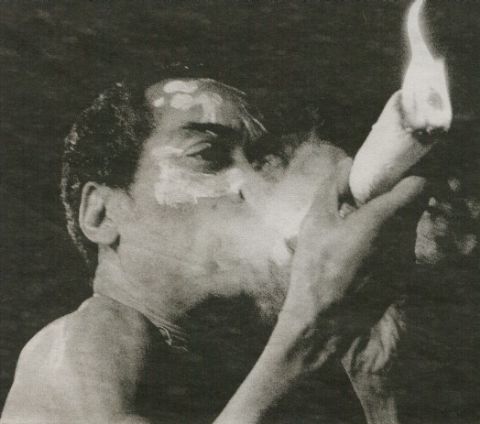

Sometime in the early seventies, in a moment of profound introspection, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti created Afro beat. Throughout his life, he promoted the music genre singing of specific injustices and eternal truths. He was the ‘rogue’ poet who protested pilfered chests, greedy statesmen and overcrowded prisons. Fela was a spiritualist, commune king, composer, saxophonist, keyboardist, dancer and most importantly, a gifted storyteller. In the wake of the 11thedition of Felabration, a yearly music fest in his honour, Olatunji Ololade, Assistant Editor, takes a journey into the life of the rebel who knew the commandments so well because he had broken so many of them.

There is not a stir, not even a faint rustle in the confines of the crypt in Kalakuta Republic, Gbemisola Street, Ikeja, Lagos. The final resting place of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Afro-beat maestro remains undisturbed as the world celebrates the music genius.

Perhaps, he lived in hope of becoming an everlasting memory, for as the world retires from the 11

thannual Felabration festival, a six-day celebration of his life and works, Anikulapo-Kuti looms large in the consciousness of music fans worldwide. It’s almost eternal, much like the commemoration of a demigod.

How important was Anikulapo-Kuti? The question beggars a surfeit of answers although it is best served by how the world took the news of his death.

The streets overflowed with tears and the indignation of his loyal fans with death. And for seven hours his funeral procession meandered through Ikeja, the working-class district of Nigeria’s Lagos metropolis, the hub of Anikulapo-Kuti’s music empire. Usually, the journey would take half an hour, but on August 12, 1997, 10 days after his death, about one million people, comprising Nigerians and foreigners thronged the streets of Lagos to bid the man known as Abami Eda (Supernatural Being) a teary bye.

During this solemn procession, one of the vehicles in the motorcade, an open truck, let out the late artiste’s classics in chunky aural waves. The music was live, from a band playing on the moving vehicle throughout the journey.

Today, the music is still live and strident enough to sustain the attention of his loyal fans while earning him the respect of even his most virulent critics.

Even in death, he lives. Famous for his copious use of marijuana, his attitude to women and his proclivity for appearing in briefs, Fela Kuti was, and is still, many things to many people; an icon, activist, a philanthropist and risqué reverend to whom music served as a tool of evangelism and a fount of inspiration.

Anikulapo-Kuti, also popularly known as Fela, was a thorn in the flesh of the ruling class; outspoken, tough and uncompromising in his denunciation of the sleaze, larceny, violence and hypocrisy emblematic of the Nigerian government since the country’s independence from her British colonialists.

Born Fela Ransome Kuti in 1938, he changed his name Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, translated into his native Yoruba to mean, “One who radiates eminence, has control over death, and can’t be slain by a mortal.”

Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, his father, was a preacher. The latter was also a teacher who headed the local grammar school and was once bayoneted by a soldier for defying the British Flag. Funmilayo, his mother, was also a teacher, though more influential as a political activist. In a country where women weren’t encouraged to speak their mind, Fela’s mother was more influential than most men, once dining with Mao Tse-tung a.k.a Chairman Mao, the late Chinese emperor.

Anikulapo-Kuti, a native of Abeokuta, Ogun State grew up in a middle-class family on the watch of parents who were strict disciplinarians.

His mother, Funmilayo, was a feminist active in the anti-colonial movement and his father, Oludotun, was the first president of the Nigerian Union of Teachers (NUT).

Later, Fela, the third of four children would claim that he received about 3,000 strokes from his parents.

His mother, Funmilayo was a huge influence on his life as she became active politically in the 1940s, being the first voice to speak out for women’s rights (mobilizing at one point 50, 000 women to speak out against unfair tax laws) earning them the right to vote and herself, the Lenin Peace prize in the early sixties.

The making of Abami Eda

It was not until 1954 that Fela’s music legacy began when he met Jimoh Kombi Braimah (JK for short) who would become a lifelong friend, and who at the time was the lead singer for a local band in Lagos called The Cool Cats. This would lead to Braimah forming a band with Fela, playing High Life and Jazz around Lagos, until the two left for London, United Kingdom (UK).

Fela’s parents had sent him to the UK in 1958 to study Medicine but he decided to enroll at Trinity College to study music. JK followed soon thereafter to study law at North Western Polytechnic. JK failed to secure admission into the polytechnic and instead, decided to form a band with Fela – The Koola Lobitos. The group would play their high-life music (much of it composed by Fela.) for fellow Nigerian students at student dances, and the like. This soon became a little more profitable when they began to infiltrate and play in the many Jazz clubs around London.

In 1961, Fela met and married his first wife Remilekun Taylor, the daughter of a Nigerian father and Black American mother, born on the outskirts of London during the Second World War. Taylor bore him three kids, Femi, Yeni and Sola and in 1963 she accompanied him back to Nigeria where Fela invented Afro-Beat.

Afro beat was his response to competition, Geraldo Pino, a Sierra Leonean who was taking Nigeria by storm. Pino was playing the music of James Brown and other American Soul artists thereby robbing Fela of his audience, forcing him to change his style before he became totally irrelevant. The local press was wooed by Fela and he called a conference where he announced that he was changing to “Afro Beat.”

Soon, he started a club called the Afro-Spot, gaining a little prestige, but not enough to conquer the more established Pino a.k.a Nigeria’s James Brown.

At that period, the atrocities being perpetrated during the nation’s civil war wrought far-reaching impression on Fela making him question his patriotism, but paradoxically, it would not be until he left for America on impulse that he would discover his politics.

After a few fruitless months with his band in New York, with no record company interest and expired visas, it was decided that a move to Los Angeles (L.A.) might yield better results. It was there that he met Sandra Isidore, a native of L.A., who changed his fortune forever. As lover, friend and colleague, Isidore, a brainy woman and an impassioned black rights activist, enlightened Fela in ways he had never been. She earned his respect almost effortlessly. A black woman who had been sent to prison for her beliefs fitted perfectly into the new world Fela was sojourning. She would also change his life by making him read The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Instantaneously, Fela decided to revise his music philosophy, ditching much of the highlife and jazz. He infused more hard funk and African chant and thus gave Afro beat, a deserving rebirth. Afro Beat was finally real.

Fela introduced his new sound to some clubs around L.A. and it was often received with slack-jawed amazement as something deep, powerful and infectious.

Enter Kalakuta Republic

With heightened purpose, a unique energy and sound, Fela returned to Lagos where he changed the name of his band to Africa 70, and began to make hits. He founded The Afrika Shrine, a new club, and started his own commune that would later become the Kalakuta Republic.

Located at 14, Agege Motor Road, Idi-Oro, Mushin, Lagos, Kalakuta Republic became a home for many connected to the band and otherwise. It had a free health clinic and recording facility and Abami Eda later declared it independent of the Nigerian state.

Fela needed a term to describe the thought process of living in a post-colonial mentality, and that’s what the republic was about.

“It was when I was in a police cell at the C.I.D. (Central Intelligence Division) headquarters in Lagos; the cell I was in was named ‘The Kalakuta Republic’ by the prisoners. I found out when I went to East Africa that Kalakuta is a Swahili word that means ‘rascal.’ So, if rascality is going to get us what we want, we will use it; because we are dealing with corrupt people, we have to be rascally with them,” he explained.

Inside Fela’s republic, recordings continued, and the music became more politically motivated. Consequently, his music became very popular among the Nigerian public and Africans in general. As a result, he decided to sing in Pidgin English so that his music could be enjoyed by every African.

However as popular as Fela’s music had become in Nigeria and elsewhere, it was also very unpopular with the ruling government. Little wonder raids on Kalakuta Republic were frequent. In 1974, the police reportedly, arrived at Fela’s domain with a search warrant and a cannabis joint, which they had intended to plant on him.

Wizened and full of theatrics, the Afro beat progenitor claimed to the officer holding the contraband, that he could not see it. He held to his claim until the joint was in his face. At that point, he snatched it and swallowed it. In response, the police took him into custody and waited to examine his faeces in order to secure evidence to prosecute him but his cell mates would wake him in the middle of the night to use the communal pail -leaving the bumbling police to wonder how their prisoner could go for so long without defecating. Another version of the story maintained that Fela enlisted the help of his prison mates who supplied him with excreta which of course, was devoid of cannabis traces.

Due to lack of evidence to press charges, Fela was freed. He then recounted his ordeal in Expensive Shit, a listeners’ favourite.

How his neighbours described him

Benjamin Adegeye, 72, was Fela’s neighbour at the period. According to him, it was interesting to observe goings on at the republic. “Many parents were concerned about the negative messages their wards could be getting. There were incessant complaints about activities and noise at Kalakuta. If anything went wrong in the vicinity, we blamed it on Fela and his boys although many of us secretly admired him and appreciated his music. Some even snuck to his shrine after badmouthing it in public. Kalakuta Republic was an attraction hardly anyone could ignore. Even if you don’t venture in to party and smoke marijuana, you would still find a vantage point to watch happenings inside and around the place,” revealed Adegeye.

Rasheed and Mulkat Balogun, 54 and 49 respectively recalled with nostalgia days they hung around Kalakuta Republic on their way to school. The couple who spent a great part of their childhood in Mushin disclosed that oftentimes, they stopped to watch, mouth agape, activities at the place.

“There was always something interesting happening at the place. It’s either a parent comes around to drag her daughter out of the place by the ear or a father comes to flog his sons for branching at the place while running errands for him. Once, a very pretty friend of mine absconded from home. After we had assisted her parents in searching for her for months, we sighted her at Kalakuta Republic. When we went with her parents and the police to get her, she refused to follow us and started calling us names. She blamed us for snitching on her. She never followed us. She is late now,” said Mulkat.

Madam Beulah Lasisi, a 67-year-old grocer and resident of the area said that, “Even though many people complained, many people still loved Fela. He said all those things everyone wanted to say and made sure the government heard them. Unlike other artistes, he sang and fought for the masses and he really entertained us while doing so. No parent should say he messed up their kids’ lives. That’s just a lie to cover up their failures. Fela wasn’t a bad person and Kalakuta didn’t destroy anyone I knew. I only know that it was destroyed.”

Death of the Republic

Indeed, it was only a matter of time before Kalakuta Republic got destroyed. It happened in 1977 after Fela and the Afrika ’70 released the hit album, Zombie, a scathing attack on Nigerian soldiers.

Fela employed derisive allegory to describe the schemes of the Nigerian military. Expectedly, Zombie became a chart stopper and smash hit with the people. On the other hand, it incurred government’s wrath hence instigating a brutal assault on the Kalakuta Republic on February 18, 1977. A thousand armed soldiers invaded Fela’s commune and destroyed it.

Fela was ruthlessly beaten, and Funmilayo, his elderly mother was thrown through a window, causing her fatal injuries.

The Kalakuta Republic was burned, and Fela’s studio, instruments, and master tapes were destroyed. Fela claimed that he would have been beaten to death if not for the intervention of a commanding officer.

Destitute and disillusioned with the nation’s justice system, Fela and the 80 former inhabitants of Kalakuta Republic spent the next few weeks sleeping at Crossroads Hotel as The Afrika Shrine had been destroyed along with his commune, and the offices of Decca Records before leaving for Ghana to promote the album, Zombie, which was also a huge hit with the students in that country. The song mocked Nigerian soldiers as mindless puppets.

Following several successful concerts, and interactive sessions with many students, Fela and his band were deported from Ghana. Subsequently, they traveled to another successful concert in Berlin, Germany (the results of which can be heard on the live album, V.I.P.).

However, on his return to the country, Fela attempted to outdo himself in his brand radicalism. In one ceremony, he married every one of his dancers and singers, calling them his “Queens.” He bestowed upon them the name, Anikulapo-Kuti. Later, he was to adopt a rotation system of keeping only twelve simultaneous wives. It was the first anniversary of the burning of the Kalakuta Republic and according to him, that was the happiest day of his life, but as it seemed to be so often in his life, it was to be very short lived.

Less than two months after, Funmilayo, his mother died as a direct result of the wounds she sustained during the attack on Kalakuta Republic. The musician’s response was both daring and poetic.

A devastated Fela declared that he intended to deposit his mother’s coffin outside Dodan Barracks – residence of Olusegun Obasanjo, the incumbent military head of state at the time (who allegedly ordered the raid on Kalakuta Republic).

Despite barricades mounted by an alert military, the coffin was deposited, and the musician and his pallbearers turned around quietly and left. Some music enthusiasts proclaimed that the Coffin deposited for Head of State remains Fela’s most powerful and emotionally charged work.

In the wake of his mother’s death, Fela also wrote, Unknown Soldier, a mockery of the official inquest that claimed Kalakuta Republic was attacked by unknown soldiers. A secondary school, Ransome Kuti Memorial Grammar School currently occupies the spot the Republic was situated.

Fela’s politics

He was a fierce supporter of human rights, and many of his songs are direct attacks on dictatorships, specifically the militaristic governments of Nigeria in the 1970s and 1980s. He was also a social commentator, and he criticized his fellow Africans (especially the upper class) for betraying traditional African culture.

The African culture he believed in also included Polygamy and the Kalakuta Republic was formed in part as a polygamist colony.

End of an era

The two years he spent in prison over, what Amnesty International described as “spurious” currency smuggling charges tragically dampened his fiery spirit.

Although records were recorded and released and concert tour commitments fulfilled, his political silence and seeming complacence instigated speculations of ill health. Visitors and those closest to him noticed his retreat into himself and a very out of character quietness.

Fela died at age 59 on August 21, 1997 in Lagos. The announcement was made by his brother, Beko Ransome-Kuti, former deputy general for the World Health Organisation. The cause of death was announced as, “Complications brought on by AIDS,” though many have since said that they feel that his ill health was due to the sheer brutality inflicted upon him by the police and military.

It was indeed a sad end for the music genius.

Fela’s shortcomings

According to Oke Ogunde, a music enthusiast and critic, Lady is a controversial album released in the mid 1970s. Fela criticised the orientation and appellation, Lady, cherished by a new generation of women. He campaigned for the retaining of the past virtues of African women, including the complete subordination to the male-folk, among others, and against the bleaching of the dark skin by African ladies.

Furthermore, despite his general views on society, some of which showed a deep understanding, he couldn’t proffer a solution to the crisis facing society in general, nor could he see the need to organise the working masses in struggle in order to end their oppression. “This was why he took refuge in mysticism, as he believed that only the intervention of the gods could bring about change,” noted Ogunde.

Another confusion in Fela’s thinking were his extreme Pan-African views on Orthodox medicine. For example, in Perambulator, he was very critical of taking Orthodox (white men’s) medicine, e.g. in the cure of Jedi-Jedi (piles); he instead advocated traditional (herbal) options.

While he was right to have made a case for Traditional Medicine, it was unscientific of him to have called for the complete abandonment of Orthodox Medicine, simply because, according to him, it was not African. Right up to his death he never believed that AIDS was real, he always said that it was the disease of the “White man.”

Fela’s heritage

According to Femi, Anikulapo-Kuti’s son by Remi – and currently, the acclaimed successor to the late Afro beat maestro- in a recent interview, growing up as Fela’s son was “very hard, very scary. The police, the SSS (State Security Service) were always following us. I was victimised in school, because of who my father was. They would say: (sneering) ‘Ah, your father smokes hemp, he wears underwear.’ I’d say, ‘Your father wears a coat and tie, he’s a slave!’ And we would start punching, and the teacher would come.”

In a chaotic world burdened with non-stop reformation, many look to music as a means of escaping the problems of the world. Fela did the opposite. His music was borne of humanity and an overriding quest to influence the tide of the tempests tormenting civilization.

According to Allen, “playing with Fela did not cost me, or hurt my career. Once, after a raid, I was in the police cell for three days, but that was nothing, didn’t matter to me at all. But my cup was full up, to the brim.”Allen said Afro beat is considered radical because of Fela’s combative reputation. “The music sent a message to the world about militancy. No one had ever done anything like that before until Fela. So it is immense,” he said.

Hardly anyone disputes that Fela was a talented musician. Till date, fellow artistes, his fans and music enthusiasts the world over still unite to pay homage to the late African music genius.

At the recently concluded Felabration festival, world class performers including Red Hot Chilli Peppers’ Flea, Baaba Maal, Amadou and Mariam, Tony Allen, his professional associate and long time buddy, Femi and Seun, his sons, D-Banj, Tunde and Wunmi Obe, Sasha and a host of other distinguished music stars gathered to pay tribute to the music legend.

Musically, Anikulapo-Kuti was a true pioneer. Politically, he was a revolutionary.

Discontented with the status quo, Fela tried to further an unparalleled state of affairs. So doing, he created his own Utopia; Kalakuta Republic. Thus he sought to perpetuate his desires as an African.

He tried to build an autonomous cultural zone, a place that literally, didn’t exist.

“Kalakuta Republic

was essentially a space that reflected his values and needs – something all too rare in the post World War II African political and cultural landscape. It was an artificial place in the midst of an artificial situation. What could be a better metaphor for contemporary Africa?” said Paul Miller of the Project for a new Kalakuta Republic.

Sometimes, almost every adjective becomes a cliché in describing Anikulapo-Kuti. However, his 77 albums, 27 wives, over 200 court appearances and a string of confrontations with the Nigerian ruling class offers a colourful picture.

Artistically endowed, cocksure, belligerent and unapologetically blunt, Anikulapo-Kuti was unusual. And he sought to create an unusual social space founded on purely African needs.

Harassed, beaten, tortured, jailed, Anikulapo-Kuti sought to divorce himself from the prevailing mass culture characteristic of his motherland to create a new republic with a different story; a gripping yarn founded on melody, and culture indigenous to the people who lived there. It’s the stuff dreams are made of.