The Home Office has been ordered to arrange for a deported migrant family to be returned to the United Kingdom from Nigeria – in a landmark ruling that threatens to undermine the UK Government’s “deport first, appeal later” policy.

Theresa May’s department will face contempt of court proceedings unless the woman and her five-year-old son are located and transported back to the UK at the Home Office’s expense by today. It is believed to be the first time that an immigration judge has demanded that the government retrieve asylum-seekers previously deported from the UK.

Asylum campaigners and children’s charities have welcomed the ruling, which could have major implications for the way in which scores of children and their parents are deported from the UK every year.

The judgment raises fresh doubts about the validity of Ms. May’s election pledge to implement a “deport first, appeal later” regime under which asylum-seekers and migrants would automatically be sent back to their country of origin unless they could prove they would be at risk of “irreversible harm”.

Last week’s ruling, which can now be disclosed by the UK-based The Independent newspaper, sets a potential precedent that the best interests and the welfare of the child should be the “primary consideration” in deportation orders, even if their parents’ case has been quashed.

Mr. Justice Cranston, sitting in the Upper Tribunal of the Immigration and Asylum Chamber, granted a judicial review of the decision to deport the pair and in a highly unusual move – believed to be the first of its kind – ordered that the Home Office organise and foot the bill for their return to the UK by today at the latest.

The Home Office has now been granted a last-minute hearing at the Court of Appeal to quash that decision, reflecting the seriousness of the case.

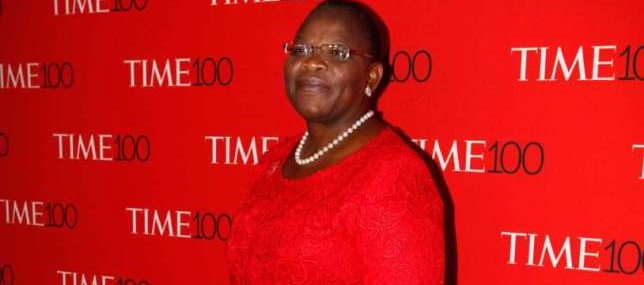

The ruling criticised the Home Office for its “flawed” decision to put the child, referred to as RA, and his 45-year-old mother BF on a plane to Nigeria at the end of January despite evidence of the woman’s poor mental health and the risk that both she and her son would end up destitute on the streets and at risk of prostitution, child labour or trafficking.

The woman claims to have been in the UK illegally since 1991 and applied for asylum in 2010, stating that she feared destitution and discrimination as a single mother in Nigeria with no immediate family.

But her asylum claim was repeatedly rejected. At one point, she was admitted to a psychiatric unit with depression and her son put into foster care as she battled against attempts to send them both back to Nigeria. The foster carers who looked after the boy and remained close to his mother have been paying for her accommodation and healthcare in Nigeria from their own savings because they were so concerned about what would happen to the pair.

The judge ruled: “In not taking into account the implications of BF’s mental health for RA, and the risk of that degenerating in the Nigerian context and the likely consequences of removal, the Secretary of State failed to have regard to BF’s best interests as a primary consideration.”