Director Niji Akanni is modest but says that, when it comes to his new film, Aramotu, modesty be damned. ‘It’s a lovely film’, he declares; and he tells NEXT why.

How did you come by the story of Aramotu?

Femi Ogunrombi, the producer, had something like a log line for the story of ‘Aramotu’. I heard the story and it sounded like a myth: that something happened somewhere a long time ago about a good woman in her community; that the woman was discovered [un-decomposed] in the grave after two weeks of burial and it was a sensation. That was what he heard and he got in touch with the executive producer, Yinka Kolapo, that it will not be a bad idea to do a film about it.

That was the spark of the story, that strange phenomenon of a woman who was buried and two weeks later they had to exhume her and they found she was still fresh. I think the original story was that there was a dispute over land and she was buried and the community said the children had to remove their mother’s corpse because she was buried on sacred ground.

I began to write my own story around it; built Aramotu up into that figure I wanted her to be. It is a story about women because I know in Yoruba history, women have always been (strong). I went back to Yoruba culture, history and myth.

Yoruba women from time immemorial are very hard working. They were actually the pillars of the society but being a patriarchal society, their contributions have always been underplayed, understated or even never acknowledged at all. At the same time, our myths give prominence to women. We venerate our women in myths but in actual history we tend to downplay their contributions to society, we tend to oppress them. So, that inconsistency between history and myth was what struck me about Aramotu. How can a culture venerate its women so much in myth, in stories but contemporary history tend to downplay them. Look at Moremi Ajasoro, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and all that.

Osun, Yemoja, they were living human beings, they actually made immense contributions to the society at the period they lived but we tend to relegate those figures to mythical proportions. We never really acknowledge what they did. Even Moremi, she is known more as a mythical figure than the activist she was in her time.

That was the impetus for creating a myth-like story of Aramotu for me. To create a woman who was a pillar of her society. And of course, it has to be a tragedy, naturally. Part of my motivation for creating Aramotu is that there are very few strong female characters in Nigerian film history. Women that can be looked upon as role models; that can be emulated, that can serve as inspiration. That was one of the reasons I created Aramotu . About seven years ago, I was part of a group that organised a film forum which aimed at examining how women are portrayed in Nollywood films. I was part of what we called Movement for Cultural Awareness. We talked about this at length: why is that Nigerian females are always portrayed in stereotypical forms? Either they are witches or they are vengeful mother in laws or diabolical second wives or mistresses. Why are there no women who are human beings first and foremost with their frailties, dreams and visions? Why are there no women you can point out and find positive values? Why are we always creating symbols instead of human beings especially from the women perspective in Nigerian films? This was one of my responses to the discourse that happened at that forum.

One of the themes I tried to explore in Aramotu is how patriarchy systematically clips women’s wings and short-circuits their ambition: by invoking ‘tradition’ ‘taboo’, myths and sometimes through sheer terrorism. This is as true before and during the time of Aramotu, as it is even today. It therefore takes an extra-ordinary woman to recognise all these and still try to rise above them.

Why are you so interested in women?

I’m in a very privileged position as a creator of history, as a creator of values and I noticed that women, especially Yoruba women are under represented. So, whatever little I can do in whatever way I can to address this, I will. 0ur women need to be properly represented. As an artist, it’s very easy to create symbols, characters that are prostitutes and husband snatchers but it’s much more difficult to create human beings.

These are part of my challenges as an artist as well. How can I create a character that will be extraordinary? That will be seen first and foremost as a person than just a character in a film? I can assure you, if Aramotu becomes a success, people will begin to question whether Aramotu lived or did not. You will love it because you don’t feel that you are watching a film, you feel that you are watching a biography of somebody who lived.

Though you have already touched on the need to portray women positively in films, which you have done through Aramotu, but there are exceptions, like Efunsetan.

I can take the story of Efunsetan and look at it from another angle. Her story as we know it today is because Akinwumi Isola took the path of demonising her. I could take the same story and make her a positive role model; it depends on the angle from which you take it. It depends on your take on the story.

But doesn’t that lead to problems of historical accuracy?

Historical accuracy, yes. But history, as the cliché goes, is written by the victors. The story of Efunsetan has been written largely by men, nobody has looked at Efunsetan as a woman. What were her driving emotions? What exactly was she looking out for personally, for her society? But the powers that be will tell the story from the point of view of the ruling class. I think if you go back into history and research it very well, you will find some other perspectives that may not necessarily demonise Efunsetan Aniwura.

And I think by doing that, it’s very necessary to start giving women their due importance in the history of our culture. They are still doing what they have been doing, they’ve been the pillars of society; the unacknowledged moulders of our vision, of our leaders. Women tend to look more to the future than men; they tend to do things that will benefit the future much more than men. Men usually think more about the present, how it’s going to help their quest for power, how it’s going to enhance their status in society. But women, they are more vision oriented; they are intuitive, they see or sense what is going to happen if we continue this way, much more than men.

How long did it take you to research Aramotu?

The basic research was to situate the myth-like story of Aramotu in actual history. All I did was to try and place her in a specific and verifiable time period in Yoruba history. I chose 1909 because I came across an incident in my research, what happened in Modakeke and Ife in 1909. The current conflict between Modakeke and Ife actually dates back to 1909. The then Olubuse asked the Modakekes to leave Ife so that was basically where I situated it. Also, I wanted it to be pre-colonial because that was very important to the mission of Aramotu.

The character I created is a traveller, she is Alajapa (itinerant trader) because of what she does, she must have seen bits of the future in her travels. The white men are entrenching their foothold all over Nigeria, especially in the Yoruba kingdom. And she travels a lot; she goes to the North, even beyond Nigeria. She goes to Niger. At that time, traders went as far as Sudan. She was part of those who travelled and a traveller happens to have a wider perspective to history, to contemporary happenings. That was what Aramotu was. I set it in a pre-colonial period, a transition period between traditional culture and the slowly seeping in, as it were, foreign influences. And being a visionary, she would be able to see that we can’t continue like this, some things have to give. What I did was situate it in history, and making it much more approachable in terms of ‘did it happen or not?’

I wanted people, after seeing Aramotu, to begin to ask themselves: did it happen? Is it true, fiction? Is it myth, is it history? I’m not going to answer the question, let the audience decide. The most important thing is that I want to create a woman that will be an inspiration even though she was located in the past; I want her story to be an inspiration for the present and possibly the future. I wanted to create a human being that you can believe in, not a stereotype, not a symbol. That was my intention with Aramotu, her character, her story and the film.

Idiat Shobande who plays Aramotu, I learnt she’s a newcomer?

Until we got on location, I didn’t know her from Adam. We were looking for an Aramotu; somebody that is fresh, that will be believable. Again, that question of believability. We had a choice of casting the so-called stars in Yoruba movies. But then I thought that no matter how good they are, it will be difficult for people to believe them, given two things: their penchant for playing themselves; and secondly; [the public] will keep seeing the actor, not the character. That was why we were looking for a fresh face and Idiat Shobande came closest. I learnt later that she had actually been in the Yoruba film industry for sometime, that she had produced one or two movies herself.

What qualities did she bring to the role?

She brought an element of trust. It’s very rare to see an actress who will completely trust a director. She read the script, felt challenged and told me later that she felt that it is a character that has not been seen in the Yoruba movie industry, that she will like to give it her best. I found that very encouraging; she understood what the character was meant to be.

Are you happy with her performance?

I’m very happy with her performance but I think she could have done more. Because she was coming from a very muddied water of performance tradition, there are certain traits, gimmicks of performance that she just couldn’t do away with. No matter how much I tried, I couldn’t break those gimmicks. But generally she did well. When eventually we had the first sneak preview, I saw it in her eyes, she didn’t say it but I saw it in her eyes that she liked what she has done and that was very fulfilling for me. To be able to have guided an actor through a process whereby she discovers something that she never had; and she acknowledged it, though she didn’t know how to say it.

Is Awo Alantakun in the film real or made up?

Awo Alantakun is totally made up, it’s my own creation. I just wanted a symbol of mystery, of elements of history and I chose the spider. For me, the spider is one of the most fascinating creatures on earth. The web it spins is like creating stories and linking them together somehow. That’s what the web symbolises for me and the spider itself, look at how many uses the web can be put to. Those were the fascinating things I found out about the spider that made me create Awo Alantakun.

You have several cults of women that are only known to women. No matter how strong you are as a man, you can never understand what it is about. Awo Alantakun is an embodiment of all I know about our cultural perspective of our women; of my own personal vision of what women are capable of if given the chance. There is so much power in them and if tapped correctly, the Yoruba race can lead the world. The Yoruba race is in Nigeria so Nigeria can lead the world. Awo Alantakun never existed, it’s a metaphor for my own vision, of my understanding of women from our history and from my own understanding of how Yoruba culture perceives and treats women.

What about the film’s portrayal of the Gelede tradition?

The Gelede is recourse to actual history, [and it] still exists. Before Western influences, we had our own socio-economic and cultural elements of social engineering. The Gelede cult is one of the most important Yoruba cultural elements of social engineering. It served as the journalists of ancient times. Actually, the Gelede cult is for women; men are the ones that organise it but women are the core. All Gelede masks are dressed as women. The Gelede cult in any Yoruba society, what they do throughout the year is that they take note of all happenings in the society and at the annual Efe Night, all the recorded happenings are brought out and relayed to the audience in form of jest. It’s a form of check and balance against abuse of power. Corrupt leaders, everything they have been doing will be brought out on that night. It’s all in the spirit of fun but at the same time they are letting you know that nothing is hidden under the sun. The recourse to Efe Night was to celebrate that aspect of Yoruba culture. Before the whites came to teach us about journalism, we had our own means of organising the society. In investigative journalism today, Just as Wikileaks is seen as a rebel, the same way members of the Gelede cult are always seen as rebels. Because what is hidden, they will want to expose and that fits into Aramotu’s profile very well. And don’t forget she is a gifted sculptor.

That’s part of my own metaphor too. In the first place, in that society a woman is not supposed to be an artist, she is supposed to be a moulder of values, not a creator. And she being a creator of values through the Gelede cult becomes an anomaly. Those are the little nuances that I tried to bring into the film. Though these elements are not in your face, people will perceive them.

How long did it take to make the film?

Let’s start from the writing. I usually tell people that the process of writing Aramotu was extraordinary within the Nigerian context of filmmaking. It’s very rare to find a someone like our executive producer (Yinka Kolapo). He believed that if he could get the right crew and given resouces and time, they will produce something fantastic. He had that vision, he pursued it and I think he has achieved it. The greatest element that works for a project is time. The financier of this film afforded us the time. This is an industry where a film financier will ask you to produce a script in five days; shoot it in seven days and edit it in three weeks and it will hit the market. Conception to release is usually, give or take, two, three months. This man was ready to wait forever to get the best out of this project and he did. Writing Aramotu, the first draft took about seven weeks, then final draft another four weeks. We shot it for about three weeks in Erijiyan-Ekiti and it took about 10 months after then for post production. That’s why I said: extraordinary. This is a project that must have gulped N15 million, that’s from what I see. That’s almost 14 months to the point that it was submitted to the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA).

What were the challenges?

Even if the financier spends exraordinarily, there must be one or two challenges. You can never get exactly what you want in terms of equipment, we had to manage what we had even though compared to other digital filmmaking format in Nigeria, it’s a large project. But still, I wish that I had more resources and time. For Aramotu to be shot in about 18 days, I think, was a miracle. If you had asked me, I would have requested at least a month of peaceful shooting. The frenetic pace at which we shot was simply destabilising. If I had more time I think I would have achieved more. But then again, 18 days of shooting in Nigeria is a luxury. It’s a luxury because over the years I have managed to establish some kind of pattern for my work. I wouldn’t shoot a film in seven days, I won’t. It’s either you give me the resouces to do it or I won’t. If you like give me N10 million to direct your film in seven days, I won’t. I can’t shoot a good film in seven days. Another challenge was breaking the performance mould of the actors. We never had time for rehearsals so it’s on the set that you begin to break this mould because they are used to certain tricks. One of them didn’t even read the script before coming on set. Meanwhile, I insisted. We gave it to them, they never read it. Even one of them had the guts to ask me to tell the story on set. Also, sticking to the dialogue in the script, most of them are not used to that. They are used to improvisation, and we had to cut that first. Apart from that, the style of acting itself. Those large, theatrical portrayal; stereotypical characterisation, we had to break it. One of my delights in Aramotu was my discovery, I will say of the [actress] who played Arike. Her name is Bisi Komolafe; she has been acting, so it’s not actually a discovery. But the discovery for me is that even within the mainstream popular actors with their bags of tricks and all that, there are still some people who are malleable. She was one of them. I think her performance is wonderful.

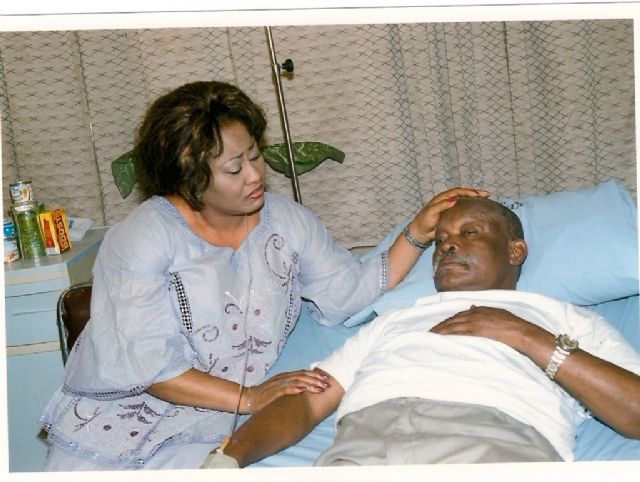

There is also Kayode Odumosu. He gave his best performance ever in his career as Akanmu, Aramotu’s husband. This is an actor I have known for 20 years, I have worked with him on stage, on screen, I’ve actually followed his career. I think it’s his best performance. Part of my luck again is that I was surrounded by a crew that knew what they were doing.

And you already envisaged what you wanted each to do?

Yes, because I wrote the script. I know the material. Before now, I used to think that the best director of a script is not necessarily its writer. I’m sure if another director takes Aramotu, he might do something much more wonderful than that. But because I wrote the script, I knew. Let me make a confession here: I actually wrote the role of Aramotu for Tina Mba. She was the actor in my subconscious when I was writing it. From delivery, to the way she looks, to what she does, to her physique, Tina Mba was my model for Aramotu. But nobody in the production team will agree with me that Tina Mba could speak Yoruba the way Aramotu should speak Yoruba. They were wrong. They were very wrong. I’m sure Tina Mba would have killed that role; she would have milked it to unprecedented heights if she was given the chance to do it. Thank God we found a substitute in Idiat Shobande. But believe me, if Tina Mba had taken that role, we’ll be talking about a phenomenon because this is an actor I know. I have worked with her on stage, on TV and in workshops, so I know her depth. Aramotu is not a role for frail actors, no. So when you see Idiat Shobande sagging a little, it’s because the weight is too much. Believe me, it was created for somebody bigger, with much more scope and range as a performer.

But there is the matter of her not understanding Yoruba?

They said so but I still believe that she could have done it. I wrote the script in English and Demola Aremu translated it into Yoruba. I have a synergy with Demola, I’ve done some works which he has translated before so he knows my language. I told him, don’t write flowery Yoruba for me, write Yoruba that people will understand, speak and relate to. The way he wrote it, I’m sure Tina could have done it.

If Aramotu eventually becomes a hit like I hope it does, I will be most happy for my executive producer. He is an engineer and he has never done this before but he believes that Nigeria’s digital film industry can do much better if given the necessary support. And that’s the support he has given Aramotu. That trust needs to be justified by Aramotu becoming a hit which is what we all want. Financially, artistically and critically. For him, that’s it. I have nothing to prove, I proved myself long before this so it’s not for me. It’s for people like Idiat Shobande; my executive producer, Yinka Kolapo; Bisi Komolafe, because if you see the kind of work she does in normal Yoruba films, you will just write her off as the usual thing. But she is not, she has so much. I wish I had the resources to say: do not work in the mainstream, I’ll pay what it is to make you live so I can retain this incredible talent and use it properly. But I don’t have the resources, then who am I to say what is not proper in film?

Your expectations for Aramotu?

I expect it to be a hit. Commercially, I expect it to be a critical success because I know what we put in it. I know it’s a good work. Yes, I’m modest but modesty be damned, it’s a lovely picture.

What are you working on now?

There are several things happening. I’m working on a play with a young man called Laide Akano about Lagos State. It’s a stage play. I’m right now editing a documentary for ActionAid Nigeria, an NGO in Abuja. I’m still working on ‘Nowhere to be Found’ for AK Media. I’m working on my PhD. My work in the theatre, especially in film now, is contributing so much to my PhD thesis because I am researching on the Semiotics of Narrative and Aesthetics in Nigerian film. So, my professional work is actually a research arm of my academic work. I’m lucky. This is actually something academics will spend time out of their walls to come and research outside. I’m doing it, I’m earning money from it and I’m storing up knowledge against my academic work. So I’m born lucky.

I noticed that you avoided saying Nollywood, what do you have against it?

It’s because it connotes mediocrity, unfortunately. It connotes mainstream, anything goes. That’s the larger perception of Nollywood. I was trained at the National Film School of India and I know the perception we had of Bollywood. Maybe I am biased but that’s the same mind I have about Nollywood. That’s the same mind most people have about Nollywood. It’s not thorough, anything goes. Nollywood has characterised itself as a platform for mediocres. Unfortunately, that’s what has happened. Historically, I was part of the founding fathers of Nollywood as it were in the early 90s but over the years it just became something else entirely. You can’t confidently say ‘I belong to Nollywood’ because it has a perjorative connotation about unprofessionalism, mediocrity, lack of vision, artistic nonsense.That’s why I feel a bit uncomfortable if people classify my work as Nollywood. Unfortunately, it is being marketed, being viewed within the Nollywood structure