Last week, I travelled from my base in Ottawa, Canada to Johannesburg, South Africa. It was one of those dreadfully long trips that I have grudgingly come to accept over the years as an inevitable feature of my professional calling as a peripatetic man of culture. As I boarded the first flight in Ottawa, I made a mental map – as I always do – of how to fill up the void of time. I had an hour ahead of me to Washington DC, nine hours from Washington to Dakar, and another nine hours from Dakar to Johannesburg.

Ain’t funny! Add to the distance the fact of not knowing how and where the pendulum of the international writing prize that was taking me to South Africa would swing. Only the thought that I would reunite with my bosom friend, Temitope Oni, a successful medical doctor in Durban whom I hadn’t seen since the end of our Titcombe College days in 1987, made the distance bearable. Tope Oni would redefine the meaning of brotherhood, human bond, and loyalty for me in ways that I am still too positively emotional to talk about. He is a subject of another essay. Another day.

Suffice it to say that in such long-flight situations, I usually oscillate between nap time, reading time, writing time (my laptop’s battery allowing), movie time, and alcohol time – with strong emphasis on the last. This time, I wish I had skipped movie time and concentrated on alcohol time. That would have spared me the agony and anger that did not abate until I landed in Johannesburg. My problem started when I picked up my assigned copy of the August 2010 edition of Sawubona, the in-flight magazine of South African Airways, to check the menu of movies.

As is the case with in-flight magazines, the movies and their summaries were classified under all kinds of genres and sub-headings. I noticed a subheading for South African movies and smiled in satisfaction. I had just found a reason to avoid Hollywood movies! I would watch all six South African movies in the package. At an average of two hours per movie, that should eat up enough hours of the trip to avoid boredom. For a second, my mind went to Goodluck Jonathan’s fleet of nine presidential jets and uncountable helicopters and I chuckled, half-wishing that our rulers would at least have the decency to have an in-flight magazine proudly advertising Nigerian movies to the President and the usual suspects who burn our money on trips with him. But that would be expecting too much from those fellows. They are usually not into such minor issues as promoting brand Nigeria unless there are contracts to be awarded.

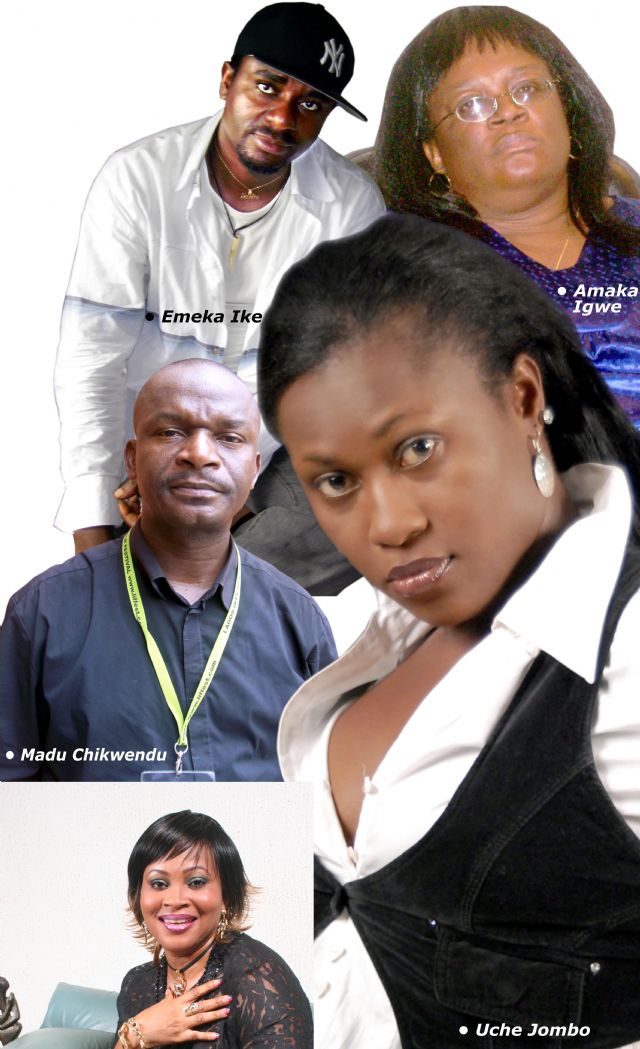

Two titles in the South African movies rubric of Sawubona immediately got my attention. Call it the itch of familiarity or the whiff of home. Call it the eponymous stirrings of recognition. Something about those titles gave me the sensation of a Molue conductor whose senses of smell and taste rev into action within a one-kilometre radius of a paraga seller: “My Last Ambition” and “Endless Tears”. Those titles screamed Nollywood, oozed Nigeria. I mean, if a movie’s got vaulting ambition in its title, we are either talking Kanayo O. Kanayo or Jim Iyke, right? If a movie says the tears are endless, there’s got to be Stella Damasus somewhere around the corner, right? If it is love with a Harlequinish tinge, you expect Ramseh Nouah, Mike Ezuruonye, Van Vicker, Majid Michel, Desmond Elliot, Ini Edo, Genevieve Nnaji, Omotola Jalade Ekehinde, Chika Ike, Oge Okoye, Stephanie Okereke, and Uche Jombo, right?

I made a mental note that I did not know that our South African friends had caught the bug of Nollywood-sounding titles. Then I watched the first movie, watched the second movie, as if in a trance, unable to believe what was going on right before my eyes. They were 100% Nollywood films alright. Not just Nollywood films. Original Nollywood flicks of the “Nnamdi Azikiwe street, Lagos and Iweka Road, Onitsha” variety. What the heck were they doing in the South African films rubric of Sawubona and being, in fact, introduced to the Washington-Dakar-Johannesburg passengers of South African Airways as part of that airline’s combo of South African films? My unease and displeasure were further compounded by the fact Hollywood and Bollywood films got their due recognition of apposite categorization in the same magazine.

Of course I have spent too much time in the scholarship and politics of cultural appropriation and mainstreaming to dismiss what was going on as a simple case of ignorance on the part of the publishers of Sawubona. It just isn’t possible that the publishers and editors of a magazine of Sawubona’s standing wouldn’t know the difference between South African films and Nollywood. I also was not of a sufficiently generous disposition to heap all the blame on that innocent and hard-working apprentice called Printer’s Devil as we always do in Nigeria.

I decided to draw very heavy conclusions from that instance of the misclassification of two Nollywood films. After all, between South Africa and Nigeria, nothing is ever innocent. There are always patrimonial egos at work, endlessly playing out in the form of a will to continental dominance, especially in the arenas of politics and culture. The two countries are locked in enactments of identity underwritten by the desire of each to be Africa’s synecdoche. In the context of the pathologies shaping relations between Nigeria and South Africa, I couldn’t even put it beyond our friends from Nelson Mandela’s kraal to expect the Nigerian cultural establishment to be grateful that they considered two Nollywood films worthy of classification as South African films and, above all, worthy to be shown on the trans-Atlantic flights of the continent’s most prestigious national carrier.

Were the South Africans to go this arifin (contempt) route, they would be well within their rights. Sadly. I don’t think we have mouth to talk – pardon that Yoru-English, it conveys the seriousness of the situation. After all, if the obtuse characters running your country prefer to organize a harem of nine presidential jets for themselves after running Nigeria Airways aground (Ethiopian Airlines has a fleet of ten jets for long range passenger services), who are you to complain if the South Africans decide to “help” by showing your films in their own national carrier albeit with a flagrant, in-your-face gesture of cultural appropriation?

The August 2010 edition of Sawubona that is at issue here was of course also in service on the Lagos-Johannesburg route of South African Airways throughout the month of August. Think of how many Nigerian state governors, senators, federal reps, and ministers would have flown South African Airways to Johannesburg in their endless money-guzzling jamborees to that country – where they learn absolutely nothing. Think of how many of them go a-partying in Lucky Igbinedion’s mansion in Johannesburg (by the way, has Dimeji Bankole been on one of his ill-reflected jamborees to that location lately?). None of them noticed that Nollywood flicks were being advertised as South African movies in Sawubona? No, not one? Imagine what would have happened if Nigeria had a national carrier with an in-flight magazine proudly displaying Zola Maseko’s fantastic flick, “A Drink in the Passage”, as a Nigerian movie! There would have been hell to pay. South African officials in Nigeria would have claimed that the sky was falling. You see, they come from a part of the world where officials of the state understand the importance of culture.

The antipathy to Nollywood and its considerable powers of cultural inflection that enabled this instance of appropriation by Sawubona is, of course, not limited to Nigeria’s obtuse rulers and the political élite. The Nigerian public’s engagement of Nollywood – at a certain informed level of national cultural conversation – is often so massively overshadowed by ubiquitous complaints of mediocrity that I have been given to think that Nollywood has no greater enemy than the Nigerian culturati. Much of the endless prattle about mediocrity – underdeveloped plot and storylines, platitudinous acting – is not borne of a constructive urge. The prattle of course ignores the fact that, unlike Hollywood and Bollywood, Nollywood arose singularly from the genius of the Nigerian people and the devastating grind of the Nigerian street, in spite of the Nigerian establishment and not because of it. The Nigerian state is always an impediment to the genius of the Nigerian people. You build Nigeria against all the odds thrown in your path by our friends in Abuja.

To have given the world the third largest movie industry right out of the poverty of Nnamdi Azikiwe street and Iweka road, with zero support from the looters in Abuja; to have created the greatest single cultural force that has not only remapped ways of seeing the continent (apologies to John Berger) in a manner not seen since Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart reshaped ways of seeing Africa in the 1960s; to have opened up avenues for global black diasporic communities to plug into the continent via the power of the image – people no longer have to wait to die one bright morning in the Caribbean for their souls to fly away home to Guinée; Nollywood brings that ancestral home to them while alive; to have inflected and changed the nature of transnational black politics while editing films in rundown shacks illuminated by “oju ti NEPA” (thanks to Dr Ola Kassim of Toronto for bringing this device to my attention); this is what Nollywood has given the world out of nothing. The South Africans certainly know what they are appropriating. And why.