After bit parts in a few Nollywood movies, our narrator makes the big time — a Nigerian soap opera. But alas, things don’t go as planned. Part 5 of 5

“Hello? Is this Williams?” The voice on the line is too loud and I have to hold the phone away from my ear.

“This is Will, yes. Who is this?”

“Hello, Williams! This is Rogers!”

“Okay.”

“I work for M-Net, the TV network. You’re a white guy, right?”

“Well, yes. Yes, I am.”

“Great! We need you to be in our new TV soap. When can we meet?”

I meet Rogers the next day in one of the popular fast food chains in Nigeria, Chicken Republic. Its prices are out of reach for most Lagosians, but that’s not the real indicator that it’s an upscale establishment. The air-conditioning whirring on full-blast is what sets it apart from most other local eateries.

A few minutes after I arrive Rogers bursts in and hugs me, excitable from the get-go. We chat for a few minutes about the show, then he takes out a video camera and films me talking for a few minutes. He says that I’m perfect (read: pasty), and that I should show up the next morning for the shoot, which will take place at LTV Studios, a reputable company that hosts local TV stations and international shows and movies. This is it! My big break.

Bimbo’s Paradox

TV soaps were wildly popular in Nigeria in the 1980s, before the onslaught from home videos. But some think that in recent years the home video market has been oversaturated, and audiences are turning back toward soaps. I’m interested to see if this is true or not.

The next day I shave for the first time in a week and put on my one suit. I even take an expensive taxi with air-conditioning so I’m not sweating when I arrive. Rogers is at the studio compound to greet me, and I’m a nervous wreck. When he opens the doors to the studio building we enter a different world from the Nollywood I’d seen so far. There are production assistants, line producers, dressing rooms (separate ones for the stars), makeup artists and hairstylists. A full breakfast buffet is served, replete with Western-style and Nigerian dishes. There is a studio set with dozens of lights and furniture and props and an art department. People huddle in corners talking self-importantly into cell phones. The only similarity to my earlier experiences in Nollywood, in fact, is that actors still have to supply their own wardrobe.

I am introduced to a dozen people and then ushered into a chair to wait for makeup. But I’m too antsy; I need to explore. I wander toward the set unattended but am quickly caught by a strict yet courteous security guard. “Let me escort you back to the green room, sir,” he says with a hand on my elbow, and guides me away from the lights and the real actors.

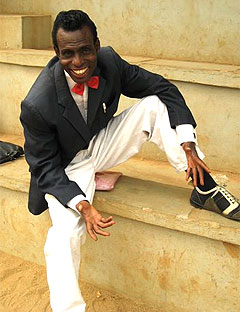

In the waiting room is veteran actor Yemi Solade, who says he’s 48 but doesn’t look a day older than 35 (and this is without Botox, which hasn’t yet made it to Nigeria, as far as I know). Trained for the stage, Yemi now spends his time acting in soaps and movies to pay the bills. He is proud that his work and the work of others in the industry has helped shed a light on Nigeria for something other than violence, corruption, and scams. “We have opened up Nigeria and Africa to the world through our videos and TV shows,” Yemi says. “People see the movies and they say, ‘Oh, there are houses in Africa? They drive cars in Africa?’”

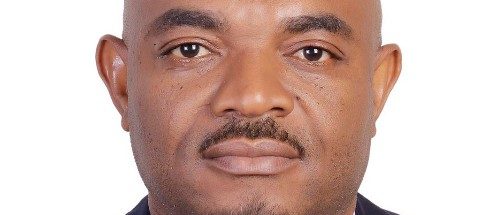

Nodding next to Yemi is another elder statesman of Nollywood, Bimbo Manuel (“Not that kind of Bimbo,” he assures me). “But the mass-produced home videos are not what Nigerian film should be judged by.” He is an aesthete, and is riled by the poor quality standards in the home videos that are produced and watched throughout the continent. “They are not a reflection of what we’re capable of. It’s a paradox, because they are what brought us attention, but that’s not all we have.”

An audience has gathered to listen to the two sages talk about their craft, but just as they’re hitting their stride an assistant knocks on the door and says they’re ready for our scene. For the first time I realize I still haven’t been given a script and have no idea what is going on. I track Rogers down and ask him for a script.

“Oh, don’t worry, you’re just an extra. You’ll just be standing in the background.”

There they go, all my expectations, right out the window. I spend the next four hours standing under bright lights with 20 other extras who must have all had dashed hopes for a starring role. We sip fake wine together at our tables while watching two actors do the same scene again and again.

The director, a serious-looking South African named Denny Miller, paces back and forth between the set and a control room. He has not looked in my direction the whole day. Toward the end of the shoot he leans over to his assistant and says, “We need two star-gazers for this scene. Who’s that guy?”

“The accountant,” she replies.

“The real accountant? The actual accountant is in my scene?”

“You said you wanted as many extras as possible.”

“Okay, fine. Let’s use him. Now we just need one more person and we can finish this thing.”

Plucked from Obscurity

They look around the room, their attention flitting from one cast member and extra to the next. My furrowed brow and sucked in “model cheeks” aren’t working. I try big doe eyes and eager smiles. Nothing. Luckily, they realize I’m the only extra who has not yet been featured in a scene. The assistant motions me over. “Excuse me, sir, can you come here please?”

Once they see me on camera they’ll want to cast me in a starring role for sure. The director looks at me nervously. “You will stand next to the accountant and eye this famous actress when she walks by. Can you do that?”

“Definitely! No problem.”

“You don’t say anything. Don’t do anything. Just stand in this exact spot and look at her when she passes.”

“Got it!”

He walks away and the assistant gets the shot ready. The accountant, standing next to me, looks as if he’s about to throw up. “Have you done this before?” he asks.

“Oh, thousands of times,” I lie, then pat his shoulder.

“Good. I haven’t. I just came into work this morning and they said they needed more bodies.”

“You’ll be fine. Just follow my lead.”

The crew adjusts the lights and the prop guys hand us our wineglasses. The makeup and lint-roller girls make their rounds and actually pay attention to me. I show them where I need a touch-up and a brush-off. I’m ready.

“Quiet on set… Tape rolling… 5-4-3…”

The actress playing a famous actress enters the shot and walks toward me and the accountant. I nudge him and suck in my gut. She stops in front of us and I begin to ogle her. I ogle her more strongly than anyone has ogled before as she says her lines. This goes on for a few takes, and the director does not come out and scold me, so I get a bit more confident. In the final shot, as the famous actress wraps up her speech, I can’t resist any longer. I raise my glass and wink at the camera.

During the lunch break I wander outside the studio building to look for Denny, the director. I find him standing at the end of the building smoking a cigarette, looking effortlessly cool in a gray V-neck sweater and jeans. All of the sudden I feel like a freshman in high school, looking for the senior to give me some attention. He doesn’t look up as I approach.

“So, that went pretty well, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“Um, do you think there’s any potential for a recurring role for me?”

He looks up and squints at me. “No. You did a good job, but that’s it. Thanks.”

Stuck in traffic on my way home, I look up at the dozens of billboards lining the road. Advertisements for soap, cell phones, and beer, and none will ever feature my pale image. Awash in self-pity, I hardly notice as a man selling phone cards to traffic-slowed vehicles is struck by an okada [a motorcycle taxi, ubiquitous on the streets of Lagos] rushing by. The man is unhurt, but is incensed enough by the contact that he needs to pursue it. He finds an empty beer bottle on the side of the road, breaks it to form a weapon, and whistles for an okada of his own to chase after the first rider. I look at my taxi driver in surprise and he smiles. “No, he won’t kill him,” he says. “Just injure him badly. Maybe stab him in the neck or stomach.”

Later that night, as I’m nursing my bruised ego with wine and saltines, Rogers calls. “Hi, Williams,” he says. “The situation has changed.” He tells me that the Hungarian man they had planned on using for the recurring white man role in the soap has moved back to Hungary and they need someone to replace him. “Are you interested?”