Kevin Cassidy, Nigeria (Hollywood Reporter)

– They call it “last-minute dot com.”

That’s how Chioma Ude describes the unique — which is a nice way of saying maddening — way in which Nigerians go about, well, pretty much everything.

As managing director of Jata Logistics, Ude should know since she assisted the organizers of the recent ION International Film Festival with getting the traveling event up and running in Port Harcourt, the capital city of Rivers State situated on the coast of Guinea Bay in Western Africa.

The decision to bring the event to Port Harcourt was the brainchild of Caterina Bortolussi and Soledad Grognett, two enterprising young women from Italy and Argentina — “oyeebo,” or “white girls,” as the locals call them — who fell in love with the country two years ago while visiting on business. As the creative director of the communications outfit Omcomm, Bortolussi is passionate about changing misperceptions about Nigeria, and she found a willing accomplice in Port Harcourt’s progressive governor, Chibuike Rotimi Ameachi.

“The governor is a very enlightened man,” Bortolussi says. “We wanted to show people that Nigeria is not what they’ve been reading about, it’s not just a place of conflict. So when we were discussing this with Gov. Ameachi, he said, ‘Why don’t we use the film festival to celebrate peace through art?’ At that point, the ION film festival was looking for a new location, so it all just came together.”

The timing couldn’t be better given the explosion in local production in recent years.

According to the results of a survey conducted by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, Nigeria is the second-most prolific film culture in the world after India, producing more than 850 films in 2006. While many of these productions are low-budget efforts that would never find international distribution, the ION Fest put a spotlight on polished, well-acted local fare like Jeta Amata’s ambitious period drama “Mary Slessor” and Izu Ojukwu’s “Nnenda,” which was awarded a “special recognition” honor at the closing-night awards gala for its portrait of a young doctor attempting to provide care to poor and abandoned children.

In addition to screening more than 80 films from around the world, 30 of which were Nigerian, the fest featured music events and workshops, including an acting session with American actor-director Giancarlo Esposito, who was here to promote his festival entry “Gospel Hill.”

Given the fest’s success at providing such a different perspective on this troubled region, ION festival founder Hossein Farmani believes the time is right to establish other film events in Port Harcourt to provide local filmmakers with ongoing support and training.

“The people here are so thirsty for knowledge,” he says. “I made an offer to the governor: I told him if he could give us a building with a long, free lease, we will supply all the equipment and training and it would be free to anyone who wants to attend. He was very open to the idea.”

For Westerners visiting Port Harcourt, a city of 1.6 million, the fact that the fest ran as smoothly as it did amid the myriad challenges the troubled region offers was nothing short of astonishing. Spend even a short time in Nigeria and the country’s glaring lack of infrastructure and organization become abundantly, some might say agonizingly, clear. From securing a visa to booking a flight at the local airport, Westerners are best advised to expect delays since Nigerians are what you might call the anti-Germans when it comes to speed and efficiency.

That said, there is no denying an undiminished spirit of optimism among the residents of Port Harcourt, who will often end even the slightest interaction with a smiling plea to “be blessed” or “enjoy your Sunday.” It’s a spirit that Bortolussi and company are gamely trying to support and foster.

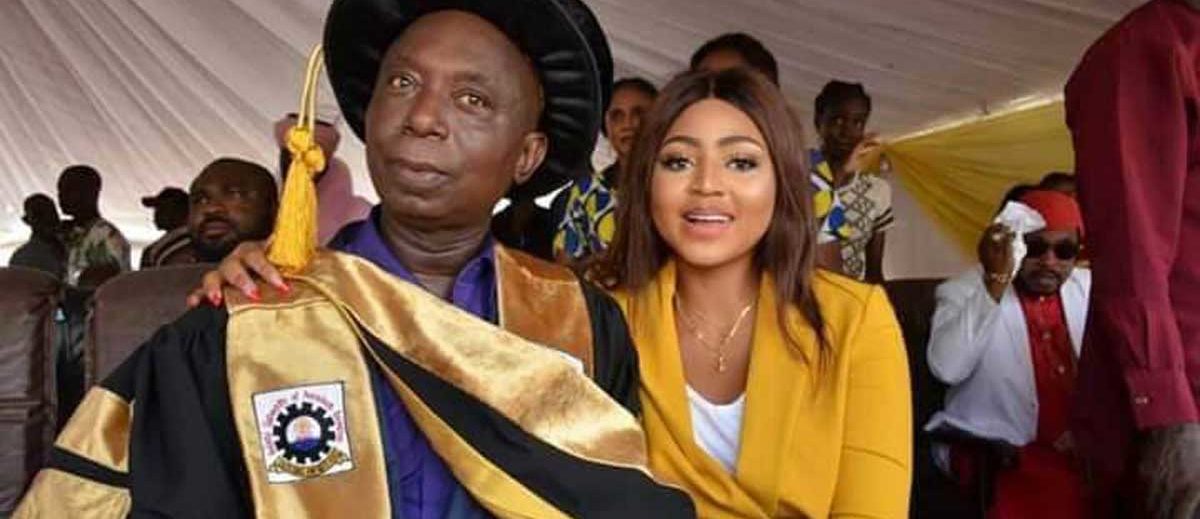

Such efforts have made Gov. Ameachi something of a local celebrity. Indeed, during the fest’s surprisingly well-executed closing-night gala, the governor, wearing a tailored purple suit and black fedora, swept in dramatically and was immediately mobbed by photographers and well-wishers as though he were a movie star. It was a vaguely surreal sight until one remembers that the governor of California, itself a troubled region wrestling with its own formidable infrastructure problems, is an actual movie star.

“At least our guy is getting things done,” quipped one proud local